Forbes.com

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com.

In the two decades since Grundfos first opened an office in China, the world’s largest producer of industrial and residential pumps has built an enviable position. The Danish company dominates the market’s high end with a share approaching 50%. Its high-quality, feature-rich pumps command prices sometimes twice as high as the local competition’s.

But if this perch atop one of the world’s most dynamic markets appears comfortable, it isn’t. Like so many foreign multinationals seeking to establish, sustain or expand their presence in China, Grundfos has found that the game has changed dramatically in recent years, forcing it to rethink old notions about how to compete.

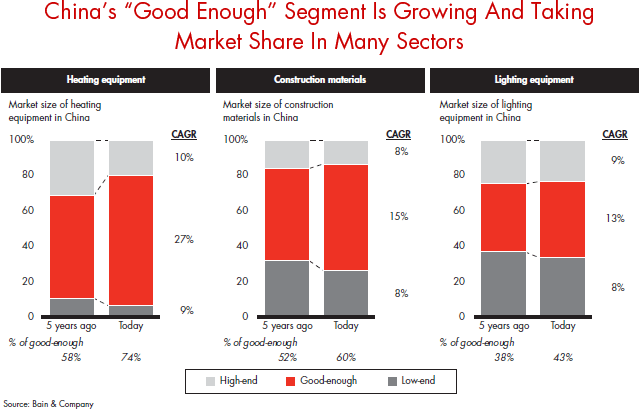

Though Grundfos continues to flourish in the market’s premium segment, it has encountered significant pressure from below as insurgent local competitors make their way up the learning curve. Having substantially closed the quality gap with well-designed, low-cost products that are “good enough” to appeal to a growing number of customers in China’s burgeoning middle market, these local rivals are scooping up market share and enticing even high-end customers to trade down for what they see as better value (see figure below).

As this pattern repeats itself in almost every market sector from construction equipment to financial information, local companies are not only posing a stiff challenge to foreign incumbents in China today but they are also conditioning themselves to compete on a global scale tomorrow. Increasingly, this twin threat demands a decisive response: For many foreign companies the question is no longer whether to take on local rivals in the “good enough” market, but where to play and how to win.

Large companies already thriving in China’s premium space have long been timid about moving down-market. Introducing lower-priced products poses the real risk of cannibalization, and many large companies lack confidence in their ability to profit in a lower-cost, fast-moving environment. But the past five years have seen a clear shift in many companies’ willingness to take on the challenge. More and more, companies like Grundfos view China’s good-enough market as a historic opportunity and are thinking creatively about how they can exploit it profitably without threatening their high-end franchises.

The most successful good-enough strategies begin with a clearly differentiated product offering that steers clear of the premium business. Companies then have to ask themselves two crucial questions: How wide is the price and feature gap between that product and our premium offerings? And how quickly can we close it with the resources at hand? The answers will vary widely depending on each company’s structure, product complexity and culture. But in most cases, this analysis will suggest three broad approaches to building a more flexible, low-cost value chain—an organic approach, which relies primarily on internal capabilities; an inorganic approach, which leans heavily on M&A; and a hybrid approach, which blends internal capabilities with external partnerships or acquisitions.

Historically, a strategic acquisition has offered the quickest, most straightforward entrée to the good-enough market. AB Volvo came to that conclusion in 2007 when it invested $80 million to buy a 70% stake in Lingong, a leading construction-equipment maker in northern China. Because Volvo’s complex global production process was highly calibrated to deliver top-end equipment at a premium price, creating a new platform to serve China posed a steep challenge. Lingong, on the other hand, provided ready access to low-cost production, a complementary line-up of popular good-enough products and a strong set of existing customer relationships.

Grundfos might have resorted to buying or partnering with a Chinese rival as well. Like Volvo, it was loath to threaten its own franchise by simply “de-specing” its premium products, and it knew that closing the price gap would require a separate, low-cost operation. But the Danish company also had a key asset that allowed it to craft a hybrid solution—a middle-market Italian pump maker, DAB, it had acquired in the 1990s.

DAB had no market presence in China but had been exporting products to other markets from a plant in Qingdao since 2006. That gave Grundfos a platform it could retrofit to create an entirely new, low-cost brand for China’s residential market called Emerco. By finding key low-cost sources for almost all its inputs and bypassing distributors to ship directly to residential installers and retail customers, Emerco products could be priced 20% to 30% lower than the premium Grundfos brand, but still 10% higher than local offerings. And Grundfos has been careful to avoid cannibalization or market confusion by maintaining a strict separation between the brands. Emerco’s website, for instance, features no links or references to the parent company.

What companies like Grundfos and Volvo are finding is that investments in China’s good-enough segment are well worth the risk. A carefully crafted strategy opens access to the vast demand being created by China’s exploding population of middle-class consumers. But they are also recognizing that the implications of the good-enough challenge stretch well beyond China. As global powerhouses like Haier and Lenovo have amply demonstrated, the skills and scale local Chinese companies develop at home eventually make them formidable competitors abroad. Winning on the good-enough battlefield is crucial to succeeding in China. But for many multinationals it may also represent the table stakes for staying competitive globally.

Read the full report: How to win on China's "good enough" battlefield

Raymond Tsang is a partner in Bain & Company’s Shanghai office and a leader in the firm’s Performance Improvement practice. Kevin Chong is a partner in Bain’s Shanghai office and leader of the firm’s Strategy practice in Greater China.