Brief

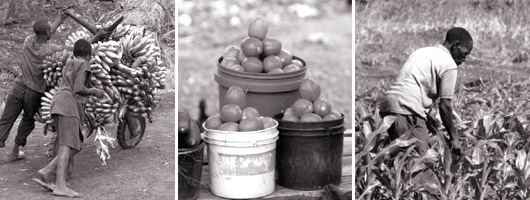

“For markets to work better for poor people, they need to facilitate the access of the poor to assets, and enable them to use these assets to generate livelihood and to reduce vulnerability.” —Making Markets Work Better for the Poor Department for International Development, 2000

So far, we have described the factors that motivate adoption from the perspective of smallholder farmers, and we have explained how the Four A’s framework and Repeatable Models can help pioneer firms systematically achieve good scale and sustained adoption. We highlighted the importance of working across the value chain to enable farmers to realize the full benefits of new innovations. In this chapter, our goal is to place our analysis of the firm, and its interactions with farmers, in a broader systems context and to highlight the important interplay among pioneer firms, the market system and major systems actors, including large corporations, foundations and development agencies, impact investors, NGOs and governments.

Firms and farmers do not operate in isolation but within a wider market system. This system can either promote the Four A’s and enable the firm to develop its Repeatable Model or it can hinder the firm’s success and slow down adoption. Indeed, due to their innovative and first-moving nature, pioneer firms are often disrupting part of a failing system. In so doing, they have the potential to initiate broader systemic change. Conversely, in some cases, no matter how successful the actions of individual pioneer firms, the widespread adoption of an innovation may be undermined by the structural challenges in the larger system in which the firm operates.

We would not attempt, in a single chapter, to do justice to the full complexity of how an agricultural market system affects the likelihood of success of pioneer firms; however, we do indicate how and where the adoption of innovation is influenced by market systems and highlight steps that those within the system can take to increase the probability of a pioneer firm’s success. Moreover, as a pioneer firm grows and begins to reach scale, its interactions with this system and other key participants within the system (including competitors), will become more central to the firm’s success. Therefore, how players outside the pioneer firm act will have an increasing influence on the long-term success of these firms and on their ability to grow to serve millions of smallholder farmers.

The agricultural market system

A system is everything that mediates interactions within a market. For the purposes of this chapter, think of an agricultural market system1 as the full range of supporting functions (such as land rights and access to personnel or finance) and both formal and informal rules of the game (like standards, regulations and laws) that impact the interactions between smallholder farmers and pioneer firms. The pioneer firm, its customers, as well as large corporations, foundations and development agencies, impact investors, NGOs and governments are all actors within the system (see Figure 27). It is how these players act that defines, and can ultimately transform, a system.

For example, trust is a major system element at the heart of every successful interaction between farmers and pioneer firms. An individual firm can enhance trust over time by the way it interacts with customers—and well-functioning standards bodies, labeling rules, effective media and anti-counterfeiting efforts all impact the way trust is experienced in the marketplace for innovative goods and services for smallholder farmers.

Whenever and wherever a specific part of the system is damaged or broken, a market will suffer: Goods will not get to the marketplace without roads; farmers will not access information without a well-developed media infrastructure; high tariffs and non-tariff barriers will prevent or delay the arrival of key firm inputs; and the absence of patent laws to protect IP will cause firms to underinvest in R&D. Similarly, even the brightest entrepreneur with the boldest idea is unlikely to successfully run a firm at scale without access to a talented pool of managers. Such personnel may be lacking because of the poor performance of the subsystem for skills training and business education. In short, the system can have a significant impact on the Four A’s—both the degree to which they present obstacles to farmer adoption and the degree to which firms can address them—as well as the ease with which pioneer firms can build and adjust Repeatable Models to fit their market.

This is why it is so important to understand how the system affects the Four A’s and the ability to create Repeatable Models. At a minimum, a strong system that supports the Four A’s is one in which information flows freely to promote awareness, operates predictably and transparently to support advantage, facilitates widespread affordability by efficient and extensive access to credit, and is underpinned by physical infrastructure that allows for access. Some specific examples of the system elements that affect the Four A’s are:

- Awareness: The existence of effective media and advertising infrastructure, like radio and written press, to provide customer education; the overall quality, transparency and reliability of information that travels through these media; the ways in which communities interact and the extent and types of interactions between one village and the next. More recently, mobile phones have played an increasing role in the rapid and efficient spread of information across communities.

- Advantage: Farmer access to complementary, high-quality and fairly priced inputs; regulatory frameworks and government policies that ensure quality standards and that can either promote or undermine the use of high-quality agricultural inputs; the existence and availability of reliable markets to which a farmer may sell his or her outputs; farmer bargaining power within that market to ensure a fair price for what he or she sells.

- Affordability: Farmer access to credit, remittances and informal borrowing; the system of taxes and subsidies, as well as other factors that affect the costs of inputs for the firm, which, in turn, affect pricing.

- Access: Physical infrastructure (roads, transportation, ports), marketplaces and trading centers; informal customs and norms that impact who can access a product or service (this may be especially relevant to the adoption of innovations by women).

The role of key actors in the system

Throughout our field work, we saw numerous examples of interactions among pioneer firms, other major actors and the system as a whole. Although we cannot hope to explore all of the complexities of these interactions, in the interest of providing actionable advice to firms and other major actors, we will share our main observations on the roles we believe large corporations, foundations and development agencies, impact investors, NGOs and governments can play to help drive adoption of agricultural innovations through enhancing the conditions of the Four A’s and enabling the creation of Repeatable Models.

Corporations

Corporations, especially multinationals, are important players in global agricultural supply chains and increasingly influence—directly or indirectly—the products and services that smallholder farmers use. As major buyers of agricultural outputs and suppliers of critical inputs, they can play an outsized role in creating realized advantage for smallholder farmers.

Corporations can provide smallholder farmers with a predictable place to sell their agricultural outputs, thereby giving these farmers more confidence that their investments in increased productivity will result in wealth increase, year after year. In fact, the demand from these multinational buyers can sometimes stimulate significant increases in economic activity in a region or country. This “market making” role of corporations is perhaps most pronounced in noncommodity cash crops like cocoa and coffee, where smallholder farmers constitute more than 80% of supply.2

However, as corporations face the reality of persistent low productivity in developing countries and the prospect of demand growth outstripping supply growth, they are realizing that securing a long-term supply of quality inputs, in the right quantity at the right price, will require a reconsideration of their procurement model. This means providing financing to smallholder farmers and greater investment in capacity-building and market services, often delivered in conjunction with local NGOs, pioneer firms or government partners, to encourage the adoption of new practices and technologies critical to increasing output productivity and quality.

A good example of these inclusive, “high-engagement” supply-chain models can be seen in the activities of Olam International, one of the world’s leading agribusinesses. Olam International is active across the value chain, from growing and sourcing to trading and processing in 65 countries. The company buys indirectly from an extended network of 3.5 million farmers worldwide, most of whom are smallholders with one- to three-hectare plots. In 2010, Olam International created the Olam Livelihood Charter for those farmers with whom the company works directly. The charter seeks to address a broad range of needs among smallholders and their communities, many of which tie directly to the Four A’s: financing for the purchase of inputs, providing seeds and agrichemicals for improved yield, training on labor practices and providing market access that recognizes a premium for quality. To date, the 20 Olam Livelihood Charter initiatives have reached more than 300,000 farmers covering more than 500,000 hectares of land.3

Among consumer product companies, Unilever, which accounts for approximately 12% of the world’s black tea purchases and 3% of palm oil purchases, has focused on building inclusive businesses and sustainable sourcing as part of its far-reaching Sustainable Living Plan.4 This plan aims to have “a positive impact on the lives of 5.5 million people by improving the livelihoods of small holder farmers, improving the incomes of small-scale retailers and increasing the participation of young entrepreneurs in our value chain.”

As part of this goal, Unilever hopes to engage with at least 500,000 smallholder farmers, particularly those within their cocoa, tea and vanilla supply chains. Specifically, in partnership with the Rainforest Alliance, Unilever has trained more than one-half of the smallholder farmers in Kenya who grow tea, the country’s largest export crop.5 Unilever is also taking a multi-stakeholder approach to engaging smallholders. In February 2014, they signed a five-year public–private partnership agreement with the International Fund for Agricultural Development to work with smallholder farmers to improve food security; they have also entered into other agreements with supplier companies, associations, development agencies and foundations.6

The investment made by Mars Chocolate in “Cocoa Development Centers” (CDCs) provides another good example.7 Through CDCs, Mars Chocolate seeks to increase the capacity of cocoa farmers and build their entrepreneurial skills by providing tools, training and techniques to cultivate high-quality crops. A CDC serves as the hub of research and best-practice demonstration for a village. Linked to the CDC are “Cocoa Village Centers” (CVCs) run by local entrepreneurs who serve as entrepreneurial role models, demonstrating best practices and selling essential agricultural goods and services to other farmers. The impact of the CDC–CVC model in Indonesia is impressive: In villages using the model, farmer yields have doubled or tripled. Based on its success in Indonesia, Mars transferred the CDC–CVC model to Côte d’Ivoire in 2010. The company has since established 16 CDCs in Côte d’Ivoire. Farmers’ interest in participating in the program has exceeded capacity: In 2013, 500 farmers applied for 35 entrepreneur roles. Understanding the importance of collaborating within the ecosystem to expand the CDC–CVC system, the company has partnered with Côte d’Ivoire’s government, leading certifiers and other supply-chain partners.

This kind of inclusive, high-engagement supply-chain model that is built harnessing the Four A’s of adoption provides an enhanced livelihood for smallholder farmers in a sustainable way, while serving the business interests of the corporations themselves. The early successes of such investments by companies like Olam International, Unilever, Mars Chocolate and Nestlé8 point to the opportunity for similar investments vis-à-vis other crop types as well. As natural resource constraints place increasing stress on global food supply, it behooves local and multinational primary agriculture buyers and producers of consumer products to systematically evaluate the opportunity to build more robust supply chains that include smallholder farmers. Ultimately, these investments will help ensure a more sustainable source of input supply for corporations while improving smallholder farmers’ productivity and livelihoods.

Whereas corporations that focus on output purchasing have increasingly considered investments in smallholder farmers to the benefit of their business, large agricultural input companies (i.e., those selling seeds and agrichemicals) seem to have found reconciling the two more challenging. The market dynamics in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia—highly fragmented, geographically dispersed customers with limited individual purchasing power—mean that smallholder farmers have largely remained a segment that is structurally unprofitable for the large agri-input companies to serve.

However, some companies are forging creative partnerships where NGOs and pioneer firms have played a key intermediary role in aggregating demand, thereby positively altering the economics for the large corporation. For example, Keytrade, a $2 billion agrichemicals company, sells high-quality fertilizer at reduced cost to OAF for use on smallholder farms. Syngenta, one of the world’s largest agriculture companies, works with GADCO in Ghana to develop rice seeds that are specifically designed for the country’s conditions and can help smallholder farmers increase their yields.

There is a great opportunity for large agriculture corporations to work more closely with pioneer firms to increase their ability to reach scale and, in turn, provide the corporations with a strong link to smallholder farmers. Corporations, by providing capital (in the form of grants or investments), expertise, networks and market access, can help pioneer firms build and scale their Repeatable Models, and, by extension, reach a large and growing base of smallholder farmer customers, more quickly and more effectively.

What we are clearly seeing is a more proactive stance on the part of major corporations to invest in smallholder farmers, either directly or through partner organizations. It reflects a growing orientation to define what is in the interest of the company in a way that considers both a longer time horizon and a broader set of stakeholders. Nevertheless, to date, the overall impact from such corporate investments remains less than what it could be for various reasons. One reason is that developing the necessary partnerships takes time, and it often requires new skills on the part of multinational corporations—skills that may not always be present in the core operating arms of these companies—as well as a well-entrenched mindset to see the shared value9 that can be created in these sorts of multi-stakeholder endeavors. Often, the appetite for initiating these programs sits more squarely in the corporate social responsibility arm of corporations, and although that can be a good place to start, the risk that companies run is that the value of these programs never fully permeates the core business.

Corporations can tackle this challenge head-on by clearly articulating the overlap between corporate citizenship and strategic market development and by addressing internal barriers to launching and scaling programs that benefit smallholder farmers and pioneer firms. This can include putting in place the right organizational capabilities to cultivate, build and manage cross-sector partnerships, as well as the necessary management incentives and metrics to encourage and sustain efforts to sell to or source from smallholder farmers. Without undertaking this work, these programs, although laudable and progressive, will operate far below their full potential scale,10 thereby compromising impact for corporations, their partners and the smallholder farmers with whom they work.

Foundations and development agencies

Foundations and development agencies are increasingly turning to the private sector to reduce poverty, seeing the potential of businesses to generate jobs and wealth, boost productivity and create market competition, while bringing innovative products and services to low-income communities. These agencies generally focus their efforts either on supporting firms directly, typically through a combination of grants or technical assistance, and perhaps increasingly channeling capital through third-party investors, or adopting systems-based approaches like Making Markets Work for the Poor (M4P)11 or Participatory Market Systems.12 In either case, interventions are most effective when they identify the system failure they seek to address and are careful that the interventions will result in a sustained solution.

Within a market, sometimes a discrete and direct intervention can fix a failing subsystem that is undermining one of the Four A’s. For example, a specific, broad-based public education campaign funded by a foundation may help address awareness, as did the Gates Foundation’s grant to IDEI that enabled it to invest in a wide range of market activation and customer education activities. This effort prepared the markets and systematically addressed a lack of awareness of microdrip irrigation products. On the back of this intervention, GEWP and other microdrip irrigation providers were able to generate sales and then sustain that awareness themselves.

However, as is the case with many interventions that are not structurally self-sustaining, once the direct intervention ceases, the program is in danger of losing momentum or, worse, reversing the good work done. In such cases, successful interventions may have to address the system’s failure more indirectly or over a longer time horizon. For example, if ongoing awareness of a new product is a major problem, it may be more effective to support local media by demonstrating how reporting on interesting innovations helps drive higher circulation or listenership. Such an approach has been successfully implemented by the UK Department for International Development–funded Enhancing Nigerian Advocacy for a Better Business Environment (ENABLE)13 program. Instead of intervening to advocate directly or fund advocacy conferences, it worked to build the respective capacity of existing business membership organizations, government, research organizations and the media to facilitate sustained public-private dialogue.

More generally, foundations and development agencies can help improve the business-enabling environment that supports the establishment of Repeatable Models. From Blueprint to Scale: The Case for Philanthropy in Impact Investing made the case that foundations and development agencies could play an important role in closing the early-stage pioneer gap by providing philanthropic capital that enables pioneer firms to test their innovations before they are able to attract other forms of capital, like impact funds. In doing so, foundations and development agencies are addressing the systems-based problem of access to capital.

What we are increasingly seeing is an ongoing role for targeted philanthropic capital, long after a company has passed through the early stages of its growth. As discussed in Chapter 4, building a Repeatable Model takes time and money. Pioneer firms need to invest ahead in people and systems and institutionalize an innovation capability to meet evolving customer needs and sustain market leadership. Grant capital is well suited to support these types of investments, as in the example of Juhudi Kilimo, which uses grants from the Ford Foundation to fund new projects. The commonality across these grants is that they are used to build scalable platforms (people development, IT, R&D) that are critical to support future growth but that do not fundamentally subsidize the underlying unit economics for the pioneer firm.

In general, we believe the best way for development agencies and foundations to improve market systems is through a combination of demonstration (building a pilot to show what is possible), supporting firm-led innovation and helping to shape the broader system by working with and through existing market players to improve their capacity. Finding the right balance of these objectives, and avoiding unwanted distortions, is the art of good program design.

Specifically, the opportunity exists for foundations and development agencies to reconsider how they can optimize the impact of their funding through a fundamentally different approach to the grantee relationship. Understandably, there has been increasing pressure on grantees to demonstrate scale and impact. However, a relentless pursuit of scale and impact by numbers without a commensurate understanding of what drives both can create inordinate pressure for premature expansion and inadvertently undermine the very organizations that grant makers are trying to support.

The sort of shift we are describing requires foundations and development agencies to be more deeply engaged in and supportive of the need to address the strategic issues facing pioneer firms: defining their core market and distinctive capabilities, assessing the robustness of their Repeatable Model and determining when they are ready to expand to product and market adjacencies. Getting this right requires a more deliberate approach, one that better calibrates grant funding and that does not push management to make potentially bad decisions. It calls for a willingness to engage with the firm in discussions about what works and what doesn’t and the openness to share lessons learned from successes and failures. It also calls for a greater understanding of the direct connection between customer advocacy, business performance and impact. Ultimately, it is through this reorientation that foundations and development agencies can best support pioneer firms to undertake the right actions in delivering on the Four A’s and building truly scalable Repeatable Models—in effect, achieving good scale.

Impact investors

From Blueprint to Scale: The Case for Philanthropy in Impact Investing profiles the important role that impact investors play in helping pioneer firms grow: to be a source of “patient capital.” Patient capital demands a return; a return indicates that a firm can grow sustainably in the long run, thereby creating value for customers as well as for investors. But it also has a high tolerance for risk, is flexible to meet the needs of entrepreneurs and accepts longer time horizons.

The importance of these long time horizons should be obvious from the analysis in this paper. Virtually all of the pioneer firms we studied either needed to engage in significant business model innovation or were functioning within broken or distorted systems that required nearly heroic efforts on the part of the firm to consistently deliver on the Four A’s across tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of customers. Within this context, patience allows the firm the time to build its Repeatable Model within a particularly challenging operating environment and it helps the firm, to varying extents, begin to redefine and reshape the system.

Thus, the role of impact investors is to take the financial risk required to give a firm time to understand the Four A’s and experiment with repeatable business models. Some impact investors are increasingly providing capital to pioneer firms, and although the goal of each individual investment must necessarily be to generate a positive return for investors, these investors must recognize that when they take risks on new, unproven business models, they are investing not only in the potential success of an individual firm but also in the potential growth of a new sector.

In addition, the daunting challenges that pioneer firms face in building Repeatable Models and adjusting them to fit the market has reinforced the need for impact investors to enhance their post-investment support, mainly by facilitating access to talent and expertise, ranging from senior personnel (e.g., board directors, mentors, senior management, subject matter experts) to more junior staff, including short-term hires. For example, Omidyar Network’s HR department helps the organizations it supports find qualified staff at senior levels. It also offers insights and guidance regarding strategy, management, operations and legal matters and opens doors to a global network of contacts. By actively sharing best practices across its investment portfolio and the wider sector, Omidyar Network (and other impact investors) can quickly disseminate lessons about what works and what does not. Last but not least, by bringing successful models to the attention of corporations, governments and the sector as a whole, they can encourage partnerships and acquisitions that will bring products and services to more customers.

The key balancing question for all impact investors is how hard to push for growth and profitability when investing in pioneer firms. More often than not, we have seen the push for scale come at the expense of companies getting their core right, and we have seen management teams and their boards of directors underestimate the complexities of expanding to new geographic areas or new product lines in agriculture. Impact investors needing to drive toward profitability and exit must balance the role they play with agricultural firms in particular, developing a solid understanding of what it takes to get the fundamentals right before a company grows.

Finally, as our paper has emphasized, agricultural pioneer firms must acquire extremely deep knowledge of their end customers. Similarly, impact investors that hope to succeed in supporting these firms must also be embedded, with strong local teams that possess the kind of knowledge that will help these pioneer firms succeed for the long run.

NGOs

NGOs frequently are already in farmers’ communities and are therefore uniquely positioned to deeply understand farmers’ needs, identify the barriers to adoption and test potential solutions to address them. As such, they can often be valuable partners for pioneer firms and even corporations by facilitating access to the challenging smallholder farmer customer segment.

NGOs can often identify and deliver the specific training required by local communities to realize the intended advantage from a new product or service. They can help build awareness by using their well-developed networks to identify likely early farmer adopters who can create the valuable demonstration effect. They can provide the information dissemination platforms to amplify subsequent word of mouth. For example, Digital Green uses videos in local languages to share information about new agricultural products, services and practices, including farmer success stories, across farmer communities. They play an even more important role in breaking through the prevailing social structures and ensuring that a product or service’s benefits are known to more marginalized members of a community who may, due to their gender, caste or tribe, not be able to interact directly with other farmers in the community.

NGOs can help corporations conduct business with smallholder farmers by aggregating them into commercially viable “units,” thereby facilitating farmer access to both inputs and markets. For example, Pradan, an India-based NGO, creates and fosters farmer cooperatives for poultry and silk production. For companies selling inputs or buying outputs, the cooperatives enable access that otherwise would be impossible if companies needed to reach smaller groups or individuals directly. The cooperatives also promote the conditions for adoption by providing training, facilitating financing and motivating the farmers to improve productivity.

Finally, a growing number of international NGOs, like TechnoServe, are providing advisory services and support to help pioneer firms develop and implement their Repeatable Model. NGOs can also use their access to smallholder farmer communities to conduct detailed customer-focused research and support the development of products and services designed specifically for farmers. Because pioneer firms often lack this access during the development stage or cannot afford the cost of research, NGOs can play an essential role by filling this void.

Indeed, several of our case-study firms were created by NGOs to fill a need identified through deep experience in farmer communities and with a recognition that market forces would provide a more scalable and sustainable solution to a pressing problem. This deep experience is the first step in building a Repeatable Model. BASIX Group’s research identified the need for extension services as critical to improving farmers’ livelihoods, which led to its creation of BASIX Krishi. IDEI created GEWP as a for-profit spin-off after its research on water scarcity in rural India identified microdrip irrigation as a viable solution. The K-Rep Development Agency, a Kenyan NGO, created Juhudi Kilimo to provide financing for income-generating assets after determining that farmers would use and benefit from this service. Sidai was founded by Farm Africa, a nonprofit working directly with smallholder farmers to share “techniques that boost harvests, reduce poverty, sustain natural resources and help end Africa’s need for aid,”14 to address the need for a better distribution and retail network for agriculture products.

The jury is still out on whether the NGO-to-firm route is the preferred method for creating agricultural pioneer firms. What we know is that it takes a long time, often years, to really understand customers and to earn their trust, something local NGOs are often well positioned to do. However, the transition from NGO to for-profit pioneer firm requires embracing a new set of constraints, a different operating model and, often, a new mentality altogether. The cultural overhang from a more traditional NGO mentality could be hard enough to overcome that a better route might be to establish more pioneer firms from the outset.

Governments

Governments are often at the heart of all market systems. No single actor has so much influence on so many of the functions and rules that affect a market. For example, the government fundamentally controls the legal ownership of land, the most primary of agriculture inputs. Therefore, a full discussion of all the possible recommendations for governments is beyond the scope of this paper. Instead, what follows are recommendations based on the discussions we have had with the leadership teams at pioneer firms and our reflections on how governments have the opportunity to help spur adoption and support pioneer firms’ success. These recommendations center on a range of key public goods critical to underpinning various elements of the Four A’s.

To support advantage, governments should establish regulations for monitoring quality, such as creating norms for packaging and standards for testing products, thus giving farmers greater confidence to try new products and services. Given the prevalence of counterfeiting of agricultural products in Kenya (estimated at up to approximately 25% of pesticides in 2010),15 both OAF and Sidai randomly test their products to ensure that what their suppliers are providing them is genuine and in the right proportions—particularly important for fertilizers and animal health products.

Similarly, the lack of quality standards and regulatory enforcement greatly hurt GEWP’s business: Multiple unregulated, unregistered companies that do not pay taxes, entered the market offering low-quality products at even lower prices. Often, farmers who had trialed these lower-quality products encountered a number of problems, like blocked or burst pipes—experiences that reduced their confidence in drip irrigation as a whole.

Governments also have an important role to play in enhancing affordability by providing, or encouraging the provision of, credit to smallholder farmers and pioneer firms.

Ready access to low-cost capital for farmers can allow them to purchase the required inputs. Many governments have realized the importance of finance in the agriculture sector and have provided incentives or mandates to banks.16

Public infrastructure investments, which help to improve farmers’ access and awareness and generally support agriculture value chains, should be thought of as “table stakes.” Farmers need roads and ports to gain access to markets for inputs and outputs, storage and cold chains to protect perishables and telecommunications and media access to broaden their awareness. Equally, government investment in research relating to agricultural technology can also enhance the conditions that promote adoption of innovations.

Governments should also carefully target investments in the form of public goods that directly benefit smallholder farmers. This includes providing extension services to farmers to help them develop knowledge required for making their farms commercially viable. Such programs should provide access to the latest technology and be available to all farmers, even those in remote locations. For example, the Kenyan government provides training and advisory services to crop and livestock farmers under its National Agriculture Extension Policy.

More generally, governments need to commit to promoting a business environment that encourages the establishment and success of pioneer firms. This means an efficient bureaucracy, predictable taxation and transparent regulation, to name just a few key conditions. Increasingly, it means government stepping in as a core customer of pioneer firms themselves, allowing for the creation of large-scale robust firms, while recognizing that end users—farmers or others—may not all be in a position to pay the full cost of an innovative product or service.17 We should not be surprised that many pioneer firms, over time and at least partially, will transition from business-to-consumer models to business-to-business or even business-to-government ones (see below). This is a transition we see primarily outside of the agricultural sector, but we expect it will permeate more sectors over time. Doing so frees up the government to play its role as a provider of public goods without having to step in to deliver on all parts of the agricultural value chain, a role that is often rife with inefficiency.

Again, these various suggestions only scratch the surface of the many ways in which governments can influence the systems that affect the Four A’s and the ease with which a firm can successfully create a Repeatable Model. However, we hope it serves to demonstrate the importance of the wider system, including the effect that a multitude of actors external to the firm and farmers themselves can have on the adoption of agricultural innovation.

NEXT · CHAPTER 6 · The long view: Why growing prosperity matters more than ever

How the pioneer firm affects the system

So far, we have highlighted how the market system can affect pioneer firms’ success and/or failure to motivate adoption. But, because these firms are a key part of the system, this relationship goes both ways. Owing to their innovative and often first-moving nature, it is not uncommon for pioneer firms to disrupt a failing system and change it for the better.

When a pioneer firm disrupts a market, it is demonstrating that something different is possible. These firms not only offer new and better ways to serve the customer, but they do so within the context of a preexisting system. In the long run, these firms are pioneering improvements to the system for all who follow by offering customer education about products and services, new distribution channels and, potentially, dialogue with government agencies to improve the regulatory environment for everyone. In this way, pioneer firms lay the foundation for the market entry of all subsequent players.

Perhaps the most powerful potential impact of pioneer firms is their interaction with the market system. For example, in 2004 Acumen investee Ziqitza Healthcare Limited (ZHL), an emergency medical care start-up in Mumbai, India, decided to expand its fleet from 7 to 70 ambulances. The company offered an “access to all” model that allowed everyone in the city to dial the company’s 1298 phone number and have an ambulance with life-saving equipment arrive within 15 minutes. ZHL not only succeeded in reaching its goal of expanding service throughout Mumbai, but also the firm’s success caught the attention of state governments across India. When these governments opened tenders for emergency ambulance service, ZHL and a handful of newer start-ups won these tenders.

Today, ZHL’s 800 ambulances serve nearly 2 million callers a year across 17 states. The company’s growth has had a significant impact on the overall health system, on the healthcare infrastructure, on the operations of private and public hospitals, on the tender process, which has become more transparent, and on a shift in perception of millions of Indians who now have fast, reliable access to emergency care. It is this level of systemic change that the most successful pioneer firms can achieve if they manage to navigate the nuanced and complex set of interactions between their firm and other actors, both within and without/beyond the system as a whole.

The ultimate value of impact-oriented capital is in the influence created when a highly successful pioneer firm manages to disrupt and transform a broader market system.

1 The analysis of market systems is well established, and our starting point is the work of the think tank and development consultancy, the Springfield Centre.

2 Based on estimates from the World Cocoa Foundation, the International Cocoa Association, the International Coffee Association, the Fairtrade Foundation and the FAO.

3 See Olam International’s website, http://olamgroup.com/sustainability/olam-livelihood-charter/, for more details.

4 See “Sustainable Sourcing,” Unilever’s website, http://www.unilever.co.uk/sustainable-living-2014/sustainable-sourcing/, and “Inclusive Business,” Unilever’s website, http://www.unilever.co.uk/sustainable-living-2014/inclusive-business/, for more details.

5 “Unilever: In Search of the Good Business,” The Economist, August 9, 2014.

6 “Livelihoods for Smallholder Farmers,” Unilever’s website, http://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living-2014/enhancing-livelihoods/inclusive-business/livelihoods-for-smallholder-farmers/index.aspx.

7 See “Securing Cocoa’s Future: Technology Transfer,” Mars’s website, http://www.mars.com/global/brands/cocoa-sustainability/cocoa-sustainability-approach/technology.aspx, for more details.

8 Nestlé’s Farmer Connect Program is creating “traceability up to farmers’ level by buying either directly from farmers, cooperatives or selective traders, applying Nestlé’s good agricultural standards, principles and practices with engagement in capacity building and training” (Hans Johr, “Creating Competitive Gaps in Upstream Supply Chains,” Nestlé’s website, http:// www.nestle.com/asset-library/documents/library/presentations/investors_events/investor_seminar_2011/nis2011-02-supply-chain-competitive-gaps-hjoehr.pdf). The program aims to increase traceability and ensure quality, safety and volume growth of raw materials while mitigating price volatility and reducing transaction costs. See “Rural Development and Responsible Sourcing,” Nestlé’s website, www.nestle.com/csv/rural-development-responsible-sourcing for more information.

9 Shared value is defined as “policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates. Shared value creation focuses on identifying and expanding the connections between societal and economic progress” (Michael Porter and Mark Kramer, “Creating Shared Value,” Harvard Business Review, 2011).

10 Nestlé trained 300,000 farmers in 2013 through capacity-building programs, and Unilever has a goal to work with 500,000 smallholder farmers by 2020. On the agricultural inputs side, Syngenta is committed to reach 20 million smallholder farmers and enable them to increase productivity by 50%. See the following for more details: “Rural Development and Responsible Sourcing,” Nestlé’s website, http://www.nestle.com/csv/rural-development-responsible-sourcing; “Livelihoods for Smallholder Farmers,” Unilever’s website, http://www.unilever.com/ sustainable-living-2014/enhancing-livelihoods/inclusive-business/livelihoods-for-smallholder-farmers/; and “Empower Smallholders,” Syngenta’s website, http://www.syngenta.com/ global/corporate/en/goodgrowthplan/commitments/Pages/empower-smallholders.aspx.

11 The M4P Hub is a good source of information for such approaches. “Introduction,” M4P Hub’s website, http://www.m4phub.org/what-is-m4p/introduction.aspx.

12 Alison Griffith and Luis Ernesto Orsorio, “Participatory Market System Development: Best Practices in Implementation of Value Chain Development Programs,” US Agency for International Development’s website, http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADP050.pdf.

13 For details, see the Enhancing Nigerian Advocacy for a Better Business Environment’s website, http://www.enable-nigeria.com/.

14 Farm Africa’s website, https://www.farmafrica.org/us/about/about-us.

15 Agnes Karingu and Patrick Karanja Ngugi, “Determinants of the Infiltration of Counterfeit Agro-based products in Kenya: A Case of Suppliers in Nairobi,” International Journal of Social Sciences and Entrepreneurship 1, no. 5 (2013): 28–36.

16 One example of this is priority sector lending in India. The Reserve Bank of India mandates that 40% of domestic banks (both public and private) and 32% of foreign banks’ net bank credit should be directed to the priority sector, including agricultural activity. Although attractive from a policy perspective, the impact of this policy on farm credit in India has been mixed. This is not surprising, since the challenge of administering such loans has prevented many organizations from extending credit directly to farmers. For example, though microfinance can work for farmers engaged in raising livestock that produce a regular income (like milk from cows), the typical weekly repayment structure presents a challenge to those farmers reliant exclusively on a harvest of crops twice a year. Some microfinance companies, like Acumen investee NRSP Bank in Pakistan, have succeeded in creating products that are tailored to the needs of these types of smallholder farmers.

17 In many countries, like India, farmers fall under a regulatory framework (e.g., the Agriculture Produce Market Committee) that sets prices and purchases on behalf of the government. In this way, the government is often a major purchaser of farmer output.