Paper & Packaging Report

}

}

Executive Summary

- Most companies aim to grow their profits at four times the rate of the market, but only 7% of industrial companies achieve this goal.

- To manage overcapacity, leading paper and packaging companies focus on improving their cost advantage.

- AI can help by transforming sales and operations planning into a continuous process, with insights constantly updated, reprioritized, and aligned across functions.

This article is part of Bain's 2026 Paper & Packaging Report.

Managing overcapacity and the low profit margins that follow is a well-known headache for paper and packaging executives. A new multiyear study by Bain & Company shows why overcapacity persists across industries: Executives are overly optimistic when they make their strategic plan.

Most companies aim to grow their revenues at twice the rate of the underlying market and profits at four times the rate of the market. In reality, only 7% of industrial companies achieve this goal. Furthermore, in capital-intense industries like paper and packaging, these optimistic plans often lead to significant capital spending and persistent overcapacity. Recent geopolitical uncertainty and tariffs have only added further complexity to the overcapacity conundrum.

In paper and packaging, leading companies do not bet on competitors scaling down or disappearing; instead, they focus on improving their own cost advantage, as overcapacity could reoccur. This might mean proactively closing capacity when necessary and avoiding the scenario in which supply so outstrips demand that players keep undercutting each other on price, until only a few can make money. For example, leading producers of graphic paper like UPM, Domtar (formerly Paper Excellence Group), Stora Enso, and Nippon Paper have all closed meaningful capacity in recent years as demand declined.

Three steps to manage overcapacity

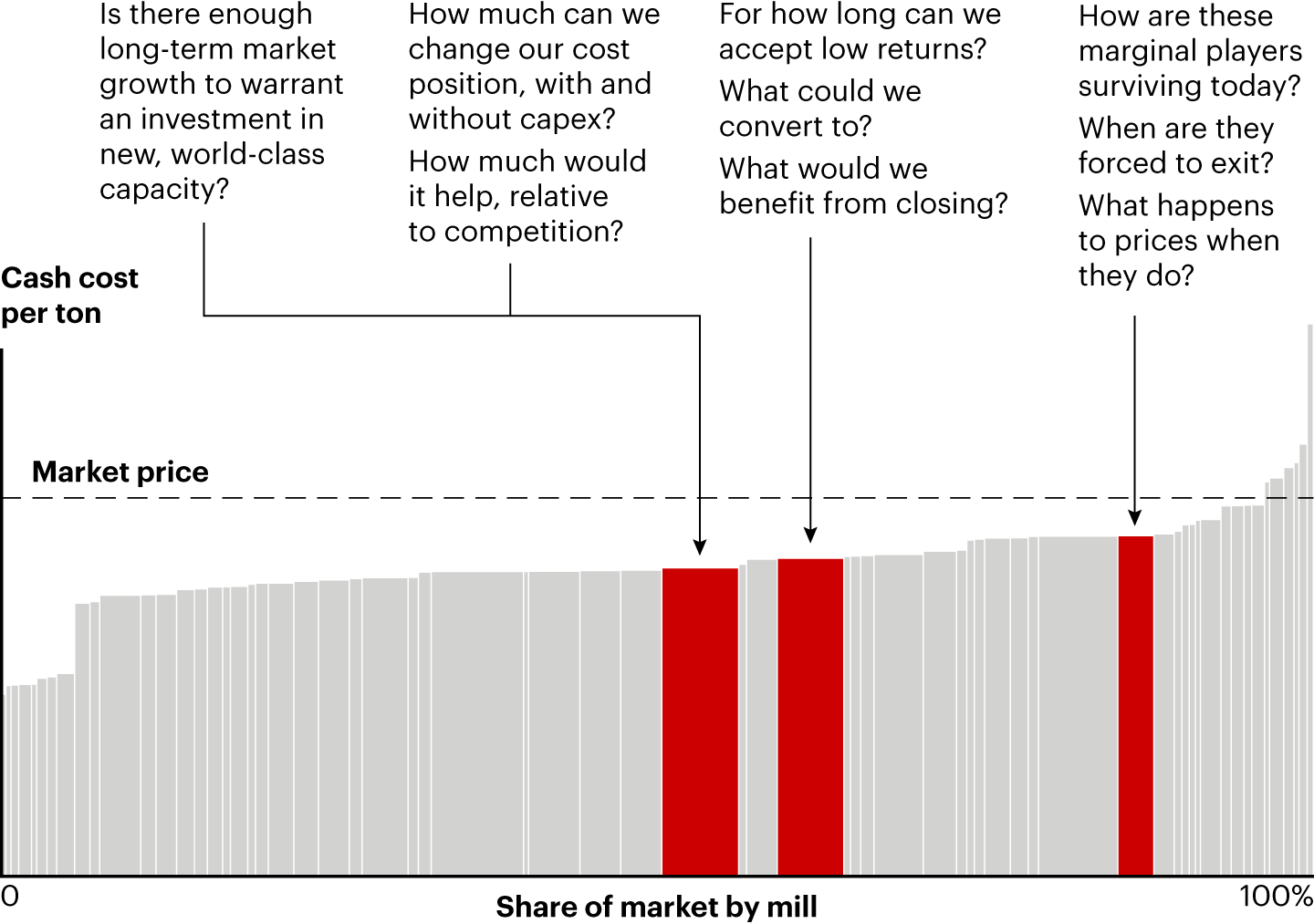

1. Understand your risk and exposure. Successful companies begin by analyzing their current and expected supply and demand balance in the grades they produce, both in the short term and the long term. They also look at their competitive position in terms of their fully landed cash cost per ton to determine: Do we have a competitive advantage, and are we also able to make money across market cycles? How sustainable is that advantage? What are our breakeven points by mill and grade, in terms of volume and price? They evaluate where a given mill or the company itself stands in the market (see Figure 1). Specifically, understanding the true end-to-end profitability of different products—and not just the contribution margin—is critical.

2. Map your strategic options, offensive and defensive. While growing scale can improve one’s position in certain industries, it’s usually not effective in creating long-term durability in paper and packaging. Instead, the cash cost position (i.e., the cost to produce a ton of board or paper) is typically what matters most. Understanding your true cost position relative to peers is hard work and requires more than relying on external secondary sources. A company’s relative cost position, for example, can change depending on the geography where it sells, as transport costs will vary, and the relative position of an individual mill is not easily understood.

In times of overcapacity, companies have a range of strategic options to weigh (see Figure 2).

Investing in capacity, efficiency, and converting to new grades. Companies that are capable of making investments often do so in competitive new capacity, such as investing in new mills or new technologies. New assets perform significantly better than aging assets, and it’s usually not possible to close that gap even by spending substantially to maintain older assets. Latin American pulp producer Suzano, for example, has invested in new assets during times of pulp overcapacity and low prices, trusting that its superior cash cost position will enable profits regardless of cycle.

Successful companies also improve their cost position by investing in efficiency. They do not necessarily add capacity but continuously push to produce every ton at a lower price. They do so by improving energy and variable cost efficiency or by using automation to lower labor costs.

Finally, they often convert to another grade where there is more room to grow than in the existing grade. They take into account the technical limitations of current assets as well as which products they could produce with reasonable investments.

Closing capacity and optimizing existing mills. Along with the high-performing mills in its portfolio, every paper and packaging company likely also has mills that are struggling. For these mills, the best option may be to close uncompetitive capacity. Closing mills usually comes with high costs and strong social considerations, making it one of the hardest decisions for paper and packaging executives.

What about mothballing, or shutting down facilities for a period to save on operational costs while maintaining equipment, so it’s possible to reopen capacity better and faster than peers when conditions change? While mothballing capacity for longer periods of time can be effective in other industries, it is relatively rare in paper and packaging. In certain segments, however, such as graphic paper and nonintegrated mills, turning production on and off is common, as it helps companies adjust to demand fluctuations and can be used to optimize electricity costs, for example.

Leading companies also focus on day-to-day operations and make their existing mill operations as cost efficient as possible without major additional investments. Still, without expending significant capital to modernize operations, even a very systematic operational excellence program will likely yield only a 7%–10% cost reduction per ton, according to Bain studies over several years. Such cost reductions are meaningful but not game-changing considering that, across most grades, top-quartile producers have 20%–40% lower costs than bottom-quartile ones.

Finally, M&A can be a useful additional tool to provide scale and to create networks of mills. With a larger footprint, closing capacity will be less challenging, as the proportionate hit of closing one mill is absorbed more easily. Lately we have seen significant consolidation in the industry, such as International Paper’s acquisition of DS Smith and Smurfit Kappa’s merger with WestRock.

3. Improve your operational flexibility with scenario planning. Leading companies are moving away from thinking about sales and operations planning (S&OP) as a traditional deterministic process for allocating demand to particular mills. Instead, they consider the different scenarios that could play out in their markets and their relevant end customer markets and ask what signposts could alert them to those scenarios. This can inform how and when they act and how they respond to competitors.

AI can also be a powerful tool in the S&OP process. Specifically, it can help transform planning into a continuous process—where insights are constantly updated, reprioritized, and aligned across functions. Generative AI, meanwhile, can deliver richer insights, increasing forecast accuracy and enabling faster, smarter decisions.

In one example, a global packaging company enhanced its forecasting system by integrating both traditional structured data—like order book information and historical sales—and unstructured or external inputs, which were previously too messy or time-consuming to use. This data included economic indicators, competitor behavior, and domain-specific signals such as industry trends and even commodity movements. Gen AI was able to parse and contextualize the unstructured inputs, transforming them into predictive features the model could use. As a result, the model improved its ability to detect early inflection points—especially in volatile sectors—before they were visible in the internal data.

The AI-enabled forecast model enhanced predictive accuracy, reducing the error rate by over 10%. That kind of precision has a direct, measurable impact on the business; it decreases overproduction, tightens inventory control, and results in fewer stockouts and better alignment with upstream suppliers.

More important, the team moved from being reactive to proactive. Planners were no longer spending their time debating the validity of the baseline forecast—they were scenario testing, stress testing key variables, and collaborating with sales and ops teams to align on risk-adjusted decisions.

While this example focuses on demand, the architecture applies just as easily to supply planning and capacity modeling in the paper and packaging industry. With the right data foundation, these models can simulate lead time volatility, factory throughput, or component availability—empowering planners with an end-to-end probabilistic view.

History would suggest that overcapacity is not going anywhere soon. To thrive despite overcapacity, well-run companies allocate more volume to the most profitable customers, products, and geographies. They consider M&A as an option to expand network coverage and improve the efficiency of their asset base. They map the options for each production site, accounting for the system-wide implications of possible closures and conversions.

In addition to understanding their own business in laser detail, leading companies understand how they fit into the larger competitive landscape. Successful paper and packaging executives employ a chess-like mentality as they plot out their own strategy, forecast different moves that competitors may make, and plan their responses in those situations as scenarios continue to evolve.