Report

1. Asia-Pacific private equity: Strong results, new challenges

For two years running, the investment environment in Asia and around the world has been as unsettled and shock-prone as it’s ever been. A turbulent 2015 gave way to an even more tempestuous 2016, as a regular cadence of macro tremors rattled markets globally. Starting with mounting concerns about Chinese debt levels, the year delivered the Brexit vote in June, political scandal in South Korea, demonetization in India and an election that minted a US president openly hostile to free trade, especially with Asia.

But if private equity (PE) investors have been bothered by the uncertainty, it hasn’t showed. Despite the building turmoil, 2016 marked the third year in a row that the Asia-Pacific PE industry has performed at historic or near-historic levels—a sign that PE performance in the region is increasingly dependent on the industry’s unique set of fundamentals. Private equity deal value in the Asia-Pacific region reached $92 billion in 2016, a pullback from 2015’s all-time high of $124 billion, but the second-best year on record (see Figure 1.1). Exit activity of $74 billion was respectable, and average returns continued to outperform other asset classes, especially among a set of top-tier firms that produced world-class results.

Fund-raising of $43 billion slightly trailed the five-year average, but that’s unsurprising given the amount of money poured into these markets over the last several years. General partners (GPs) are working with near-record levels of unspent capital, and investors appear to be waiting for funds to work off some of that dry powder before renewing commitments. What’s important in terms of gauging investment confidence is that the maturing Asia-Pacific industry has locked in on the virtuous capital cycle: Limited partners (LPs) have been cash-positive in the region over the past few years, meaning GPs continue to find ways to return more capital to investors than they are drawing down for new investments. All signs indicate that LPs remain bullish on the market.

As encouraging as these results are, GPs focused on the Asia-Pacific region will also face some stiff challenges in the years ahead. In an age of superabundant capital, competition is coming from a wide variety of players, including sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), pension funds and large corporations, such as China’s BAT companies (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent). An abundance of buyers makes it increasingly difficult to find attractive proprietary transactions in the Asia-Pacific region. That has helped drive already steep Asia-Pacific multiples to unprecedented levels, even as GDP growth slows across the region and interest rates begin to rise, blunting two powerful sources of value.

At the same time, the relationship between GPs and LPs is becoming increasingly complicated as large institutions and sovereign wealth funds devote more and more of their PE allocations to direct investments and coinvestments. This is nothing new. Large sovereign funds such as Temasek and GIC in Singapore and Khazanah in Malaysia have been major factors in the market for years. And big foreign funds like the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB) are becoming more so. But the growth of this so-called shadow capital is testing relationships between GPs and their investors by putting them in direct competition with each other in some cases and reducing GP economics in others.

There’s no doubt that coinvestments with SWFs and other large investors create opportunities for GPs to burnish relationships with these massive sources of capital while participating in deals that might otherwise not be available to them. But as shadow capital grows in the market, it becomes increasingly critical for GPs to understand how to turn it to their advantage.

The combination of heightened competition, inflated multiples and a slowing macro environment hasn’t removed the ample opportunity to earn superior returns in the Asia-Pacific region. But it does mean the sources of profit are changing. While funds operating in these markets have long been able to count on economic growth and multiple expansion to power returns, those days may be over. Growth in the region remains strong by global standards, but multiples are exceptional, too. This means that GPs will have to work harder than ever to find good companies, create new value and exit them with market-beating returns.

As we’ve discussed in previous years, the stakes couldn’t be higher. While capital continues to flow steadily into the region, it is landing with those PE funds that can demonstrate sustained, market-beating returns. These same funds are also the ones most likely to appeal to big LPs as coinvestment partners. At a time when the industry’s sources of profit are changing, we find that the best GPs are focused on shoring up three key areas of the PE value chain:

- Smarter sourcing, including enhanced local networks, to find more proprietary deals and develop the differentiated insights necessary to gauge risk, assess potential and gain the confidence to outbid rivals at auction.

- Enhanced due diligence that views the target holistically, incorporating advanced analytics and a thesis-based approach to develop the kinds of insights that give a fund the ability to weigh risk and measure value effectively.

- Creative post-acquisition value enhancement to overcome two major challenges to effective portfolio management in the Asia-Pacific region: a preponderance of deals featuring minority stakes and a marketwide talent shortage.

In Section 2 of this report, we will break down in greater detail how the PE industry’s performance unfolded in 2016. In Section 3, we will open the discussion to the key trends that will shape the PE landscape in the coming year and beyond, including a look at each local market in the region. In Section 4, we will provide some of our best thinking and observations on how the most successful funds are preparing themselves to thrive not just on growth and multiple expansion, but by executing more effectively at every stage of value creation—measuring potential at entry, adding value during the holding period and ensuring a growth story at exit. These are heady days for Asia-Pacific private equity. The best firms are already preparing for challenges ahead.

2. What happened in 2016?

Given the extraordinary 39% surge in Asia-Pacific deal value in 2015, it’s hardly surprising that activity in 2016 backed off somewhat. What is impressive, though, is that the market continued to show strong momentum in most phases of the business. Deal making over the past three years has risen to a new level and shows few signs of retreat. LPs continue to view the Asia-Pacific region as an emerging market with big potential. Here’s how the year unfolded.

Investments: The momentum continues

Besides the inevitably difficult comparison with a stellar 2015, there were plenty of reasons to expect that deal making might be disappointing in 2016. We listed some of the most obvious market shocks in Section 1, but headwinds were already evident as the year began—most notably slower GDP growth in China, continued volatility in its equity markets and broad uncertainty about how the world’s second-largest economy was being managed. The PE industry, however, chose to focus on those areas where growth is clearly evident. Investment value totaled $92 billion, and the number of deals hit 892, both measures representing the second-highest totals ever (see Figure 2.1).

A combination of factors fueled the strong activity, including an abundance of capital, a hot Internet sector and the continued buying power of large institutions and SWFs. Funds in the region began the year with $137 billion in unspent capital and ended it with $136 billion, or almost two years’ supply at the current pace of investments (see Figure 2.2). While this created a strong incentive to put money to work, GPs for the most part showed great restraint in the face of inflated asset valuations. The exception was their continued appetite for high-growth technology companies. Internet, technology, media and telecommunications companies attracted $42 billion, or 45% of total investment value last year. Internet deals alone accounted for more than a third of the total, continuing a five-year trend (see Figure 2.3).

This focus on innovation provided a strong foundation for investment activity. Indeed, in April, Alibaba Group’s Ant Financial Services unit attracted the largest private fund-raising round for an Internet company ever, when sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corp. (CIC) and others invested $4.5 billion in the digital payments and financing platform. Megadeals, however, had less of an influence on investment totals than in previous years. Except in Japan, where Kohlberg Kravis Roberts’ $4.5 billion buyout of auto parts maker Calsonic Kansei Corp. was the largest PE investment ever in that country, megadeals fell off sharply from 2015—especially in China (see Figure 2.4).

Early-stage deals, on the other hand, surged largely due to Internet fever. As GPs seek out growth and the region becomes increasingly comfortable with the PE value proposition, the number of small-company deals has risen steadily in recent years. The value of early-stage deals rose to $16 billion, or 18% of the total market, with particularly strong activity in Greater China, where early-stage deal value rose 24% from 2015 and was three times higher than the past five years’ average (see Figure 2.5). Activity ran the gamut from a $600 million second-round financing of electric car company Singulato Motors by Beijing’s Lancapital Holdings to GGV Capital’s $60 million Series B financing round of Zuoyebang, an online education company spun off from China’s Baidu Inc.

The wave of capital chasing deals of all sizes has kept competition at a fever pitch, which in turn has pushed valuations into nosebleed territory (see Figure 2.6). The average multiple of EBITDA-to-enterprise value for PE transactions in the Asia-Pacific region climbed to 17 in 2016 from a record 16.6 in 2015, dwarfing the average of about 10 for US transactions. High-priced deals in China, where overall M&A multiples rose to almost 30 from 26 in 2015, created the most upward pressure. But heavy competition and a limited supply of high-quality targets have inflated prices throughout the region for years.

Although transactions involving large institutions and SWFs were less prevalent in 2016, these massive investors are catalyzing the deals that grab the most and biggest headlines in the Asia-Pacific region. Over the last five years, transactions involving some form of direct LP investment made up 29% of all Asia-Pacific deals and a stunning 57% of deals with $1 billion or more in value (see Figure 2.7). That compares with just 18% globally over the same period. As we’ll discuss more fully in Section 3, this poses both opportunities and threats for GPs operating in the region. But given industry dynamics, it’s clear that shadow capital is here to stay.

Exits: Still healthy, if less robust

With multiples soaring in the Asia-Pacific region, it was clearly a good year to sell companies. But Asia-Pacific exit value dropped to $74 billion in 2016 on only 418 exit transactions, as both measures fell below the five-year averages (see Figure 2.8). Despite the massive $7.4 billion initial public offering (IPO) of Postal Savings Bank of China, exit value in Greater China dropped 34% from the 2015 total, primarily because of a soft public equity market and subdued M&A activity. A few large exits helped to push the numbers higher in India, Southeast Asia and South Korea, but on a narrow base. Total volume in these markets benefited from an unusual number of very large transactions, such as Affinity Equity Partners’ and SK Planet’s $1.6 billion trade sale of Korea’s Loen Entertainment and KKR’s $1.2 billion exit of India’s Alliance Tire Group.

A deeper look at the exit numbers suggests that the region was due for a break. After a few years of exits well above average, GPs have trimmed back an overhang of older companies in their portfolios, leaving themselves fewer ripe assets to sell. From 2008 to 2014, a lack of steady exit activity in the Asia-Pacific region allowed unrealized value to grow 27% compounded annually, setting a new record each year. Stronger exits in recent years, however, have slowed that growth by two-thirds. Overall, more than 80% of the 118 GPs in Bain’s 2017 Asia-Pacific Private Equity Survey said they aren’t particularly concerned with the number of aging, unexited companies in their portfolios (see Figure 2.9).

Fund-raising: A slow year

After allocating $115 billion to funds focused on the Asia-Pacific region over the previous two years, it’s unsurprising that investors looked elsewhere in 2016. Total funds raised in the region dropped almost 16% from a year earlier to $43 billion and slipped to 9% of the global total from 11% in 2015 (see Figure 2.10).

Results from the Bain Private Equity Survey indicate that GPs sitting on a mountain of dry powder may not have been giving fund-raising their full attention during the year. Their priority has been buying companies and working on their existing portfolios—not beating the bushes for fresh capital. That may change in the coming year, however. Deals and portfolio management will continue to be priorities, but many GPs indicated they will be refocusing on fund-raising as well. Close to 70% said they will launch a new fund in the next 12 to 24 months.

What they are likely to find is that investors are becoming pickier about whom they want to work with. As in previous years, LPs favored the largest, most successful funds in 2016, and that’s not likely to change. Data shows that about 21% of Asia-Pacific PE funds that closed last year raised their capital in 12 months or less, and the most experienced funds met their goals the fastest (see Figure 2.11). For other funds, the sales process was considerably more arduous—especially first-time funds, which were on the road for more than two years, on average.

Returns: The gap widens

Performance, of course, is what drives investor interest, and for the past several years the Asia-Pacific market has delivered. Funds focused on the region have posted median internal rates of return in the 12% range for two years running, and top-quartile funds have been producing returns of closer to 20%. Most importantly, GPs in the region have made a regular habit of distributing capital. As we noted earlier, LPs in the region have been cash-positive for the past few years. For the first half of 2016, LPs got about $1.4 back for every $1 called (see Figure 2.12).

On a relative basis, the industry clearly outperforms other asset classes. The gap is substantial for every period from 1 to 20 years, which isn’t lost on investors. Surveys show that portfolio performance in the Asia-Pacific region over the past three years has largely met or exceeded the expectations of LPs and, as a result, almost 80% of those surveyed said they plan to allocate at least the same amount of new capital to the market in 2017 as they did in 2016. And 38% said they would increase their allocations (see Figure 2.13).

More than any other PE market globally, however, performance in the still-maturing Asia-Pacific region varies widely. The gap between top and bottom performers is wider in this region than it is anywhere else in the world. The differential has been widening for years—a vestige of the gold rush period before 2008, when capital flowed into the region liberally, propping up thousands of funds that are now slowly failing (see Figure 2.14).

That trend will likely continue as generating alpha in the Asia-Pacific region becomes ever more challenging. More competition, sky-high multiples and moderating economic growth mean only the most accomplished funds will find ways to create new value and generate the kinds of returns that attract fresh capital. In Section 3, we will examine these challenges in more detail and discuss how changes in the PE market will require new approaches to sourcing, due diligence and value creation.

3. The changing shape of Asia-Pacific private equity

For much of its history in the Asia-Pacific region, the PE industry has leaned toward a relatively simple value-creation formula: Look for a hot sector or market that is likely to benefit from strong macro conditions or multiple expansion, buy a minority stake in a representative company, wait for top-line growth to kick in and exit at a premium. Funds have put less emphasis on active portfolio management largely because minority stakes make it difficult to get directly involved in management and value creation. The limits of this approach became clear during the global financial crisis, when growth slowed, and aging, subpar companies piled up in regional portfolios, creating a massive exit overhang. But GPs have whittled away at the overhang in recent years and continue to benefit from the top-line growth that the good companies in emerging markets tend to generate.

The search for new sources of value

As powerful as the growth story is in the Asia-Pacific region, however, there are many reasons to believe that generating returns at current price multiples will only get tougher. Competition for deals is likely to burn hotter in the years ahead. More than 80% of the GPs in our 2017 industry survey said that they feel the current level of competition has increased. They are most worried about pressure from other regional and local PE funds, as well as strategic corporate buyers looking for opportunities to expand their footprint in the region (see Figure 3.1). As we noted earlier, this has helped push valuations into the stratosphere, increasing the pain for GPs who are looking to put dry powder to work (see Figure 3.2).

The flip side of multiple expansion, of course, is that it can help create value at exit. But it’s not clear that dynamic will hold in coming years. While competition for deals may sustain upward pressure on multiples, other factors may act as a cap on further growth. That means sellers may not be able to rely on pure multiple expansion as a source of exit value in the future.

The interest rate environment is the first problem. Since the global financial crisis in 2008, rock-bottom rates and a flood of cheap capital have contributed significantly to the Asia-Pacific region’s extraordinary multiple growth. But after a decade of global easing, interest rates in the years ahead have nowhere to go but up. More than half of the respondents in Bain’s 2017 survey believe rising rates will exert downward pressure on multiples. And that will likely create headwinds at exit for companies bought at current prices.

The other factor in flux is economic growth. While the region’s diverse set of economies remain vibrant by global standards, economists expect average GDP growth to moderate in the coming years. That, too, could act as a brake on multiples.

This means that the sources of value that Asia-Pacific investors have long counted on are shifting. Revenue growth has always been the No. 1 source of value in the region, and GPs in our survey believe it will remain so in coming years (see Figure 3.3). But while almost a third of respondents cited multiple expansion as a top source of returns five years ago, few expect that to contribute much value five years from now. Instead, 37% expect cost control and margin expansion will drive the most value, while 21% are counting on M&A activity to help improve returns.

What we know, however, is that most PE funds around the world are not particularly good at margin expansion. While deal strategies often include aggressive margin-expansion goals, GPs are less often successful in reaching those goals. Bain recently looked at a subset of post-financial-crisis deals in its proprietary database and compared deal model forecasts with actual results over the holding period. Though most had relatively accurate projections of revenue growth, 69% of them failed to attain the projected higher profit margins (see Figure 3.4). In most cases, margins actually declined during ownership. This wasn’t an Asia-specific grouping, but more than half of the emerging Asia GPs in our survey indicated that they also have struggled to meet margin-expansion goals.

The implication from this analysis is clear. As the sources of value in the industry shift, GPs will need to add new capabilities and exercise new muscles to remain competitive. While buying high and selling higher has been a reliable strategy in the past, funds will have to work harder in the future to create new value from the inside out. As we’ll see in Section 4, the best firms are focused on a few key strategies to better identify and capitalize on those opportunities.

Shadow capital: Increased complexity

As GPs think about how to adjust to new sources of value in the Asia-Pacific PE market, the most proactive firms are also devising strategies to manage the growing complexity posed by shadow capital. These firms are working from the conviction that direct investment and various forms of coinvestment by large institutions and SWFs are not passing trends, but represent a new normal in the marketplace. Limited partners are asking for—and receiving—these sorts of arrangements with ever greater frequency and, for GPs, that has critical implications for fund economics, availability of capital and access to deals.

What’s clear is that most large LPs are intent on changing how they engage with PE firms. They are reevaluating the number of GPs in their PE portfolios and seeking to generate more value from those they retain (see Figure 3.5). The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) is a prime example. In 2005, according to the Asian Venture Capital Journal, CalPERS had a PE portfolio of $9 billion placed with 275 managers. By 2020, it expects to have $20 billion in PE exposure, but wants to have only 30 GP relationships. As more LPs make similar decisions, relationships with a smaller set of favored GPs will become both closer and significantly more complex. Many GPs are viewing these changes with trepidation. But the best are making the choice to get out ahead of the trend rather than let it roll over them.

GPs in the Asia-Pacific region were split down the middle when we asked them if shadow capital poses an opportunity or a threat. But almost 80% of them already offer some sort of coinvestment to LPs, and most are planning to expand or maintain those opportunities in the future (see Figure 3.6). There are obvious reasons why LPs are asking for these relationships. Not only do they give investors more visibility into their investments and more control over outcomes, but coinvestment arrangements can offer the LP sharply reduced costs in the form of lower fees and carry.

This, of course, is the downside for GPs, as it can significantly reduce their economics and slow down the investment process. The upside: These relationships can strengthen ties with LPs, which gives PE firms better access to deep pools of capital when it’s time to raise a new fund, as well as access to large deals that might not otherwise come their way.

More troubling is a parallel trend in which LPs are investing directly, bypassing GPs altogether and competing head to head for deals. At the moment, solo direct investing is limited to a small number of institutions with the requisite heft and ability to mount such programs—notably, the largest funds in Asia, the Middle East and Canada. But when they do show up, in the absence of fees and carry, they can afford to pay a higher price and still achieve target returns.

As we’ve noted, top firms are proactively setting themselves up to make the most of the shadow capital trend. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, but some GPs are creating funds that mimic the style of larger, more conservative LPs by seeking out lower-risk, lower-return assets that they believe will hold for up to twice as long as the typical 10-year life of a conventional fund. Such funds enable GPs to compete on equal footing with institutional investors at auction, but a key challenge is deciding on the economics for these vehicles and how to adjust investing accordingly.

The most effective way for GPs to gain leverage in these situations is to improve their performance. That means sourcing more effectively, analyzing opportunities with more precision and delivering on a proprietary strategy to create value. In the next section, we’ll look at strategies that can help funds raise their game in these areas.

Private Equity in Asia-Pacific 2017

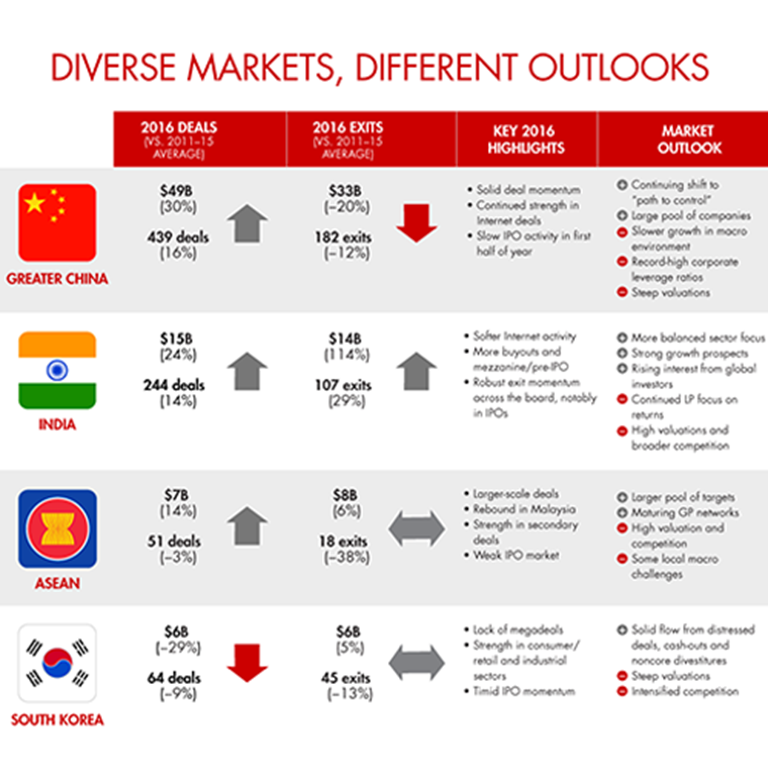

A look at the private equity highlights from last year and the outlook going forward in Greater China, India, Southeast Asia, South Korea, Japan, and Australia.

4. Creating value in a fiercely competitive market

Despite the gradual slowing of economic expansion in the Asia-Pacific region, top-line growth will continue to be a central focus of most value-creation strategies. But, as we saw in the previous section, other sources of value are becoming increasingly important in markets where asset prices have never been higher. In today’s fiercely competitive deal environment, the most effective general partners aren’t willing to rely on growth alone to produce returns. Instead, they aim to develop a differentiated angle on markets and companies by building new muscle in three critical areas:

- Smart sourcing

- Thesis-based due diligence

- Proactive value creation

Excellence in these critical capabilities gives PE firms the ability to find more proprietary deals and the confidence to set a price in bidding situations that will lead to real value.

Smart sourcing

When we asked GPs about sourcing in this year’s Asia-Pacific PE survey, a few things stood out. First the good news: Almost half of their deals are still proprietary, which means GPs in the region are avoiding expensive auctions in many cases. Finding attractive deals, however, is getting harder and harder—almost three-quarters of the respondents said it was one of their most pressing challenges (see Figure 4.1). Part of this difficulty owes to sky-high multiples in these markets, which are making it hard to justify many transactions. But it may also be that many PE firms aren’t putting their best foot forward. In our survey, few GPs said they are operating at full potential when it comes to the various aspects of sourcing (see Figure 4.2).

The firms that do excel in this essential phase of the PE value chain stand out in two key areas: They have defined a sharp point of view on where to hunt, based on their unique experience and capabilities. And they have spent years nurturing a deep and rich network of experts and market contacts, people who can help the firm proactively identify opportunities that others may miss.

Narrowing the firm’s aperture. Creating a differentiated point of view on assets starts with concentrating on what the firm does best. Firms need to clearly articulate an investing sweet spot by analyzing past successes and taking a hard look at what capabilities the team brings to the market. This sweet spot provides clear criteria that deal teams can use to filter prospects across sector, geography and deal size or type. It also suggests what sort of network the firm needs to build and which capabilities demand the most attention. That puts the firm on solid ground, ready to proactively seek out opportunities in the areas where it is most likely to succeed.

The most clearly developed sweet spots become brands that improve deal origination by announcing the firm to company owners and intermediaries who are looking for equity financing. A good example is Catterton, which developed deep expertise in the consumer sector before partnering last year with LVMH and Groupe Arnault to form L Catterton. The partnership bills itself as “The World’s Leading Consumer Growth Investor” and is building a proprietary investment process to define key consumer trends and investment themes before matching them against a set of defined industry verticals from luxury apparel to household durables. The objective is to narrow the funnel down to subcategories before the firm identifies and prioritizes a set of attractive, midmarket growth targets. L Catterton can then offer those targets a valuable set of enticements, including sector-specific operational expertise, access to a network of strategic thought leaders and the ability to tap a deep pool of consumer industry talent.

This kind of sharply defined focus on a sweet spot enhances a firm’s ability to double down on areas where it can bring the most value. Deal teams can build a live list of companies evaluated on a predetermined set of criteria and approach owners to develop relationships long before they are ready to sell. A clearly stated direction motivates action, giving teams incentive to mine the firm’s key areas of interest for leads and relationships.

Kiki Yang, a partner in Bain's Private Equity practice, outlines three things successful general partners are doing to compete in the active private equity sector in Asia-Pacific.

Building strong networks. GPs in the Asia-Pacific region say intermediaries and internal networks built by managing directors provide their biggest sources of deal flow. Networking, by definition, is an individualized, high-touch process that should align with the firm’s personality. For Bain Capital, that means carefully defining where it wants to play, based on macro analysis and its ability to take advantage of global expertise in various sectors. It then screens and proactively contacts key players in the short-listed areas of interest. In 2014, that led the firm to Asia Pacific Medical Group (APMG), a private hospital company in China. After the initial introduction, the Bain Capital deal team slowly built trust and rapport with APMG management and shareholders, using its network to secure access to key decision makers. In March of last year, the persistence paid off. Bain Capital turned an original deal to supply minority growth capital into a $150 million buyout of APMG, giving the firm’s new Asia fund a solid position in China’s fast-growing healthcare sector.

The best firms also build relationships strategically and proactively, based on what sorts of expertise will complement their own. They involve the whole team, including junior staff, in securing connections within key industries and geographies. They hire senior industry leaders to help source deals and nurture relationships with the investment banks and other deal intermediaries that orbit their sweet spot.

Because reputation and familiarity matter deeply when building in-market connections, many firms also tap highly respected individuals with local star power to help establish a brand and enhance networks locally. In 2011, for instance, KKR appointed Lim Hwee Hua, Singapore’s former minister of finance and transport, as a senior adviser. Last year, Wendel Group sought to enhance its network in Southeast Asia by hiring former HSBC Indonesia Managing Director Ted Margono as an adviser. These experts can create credibility in local markets and open doors by facilitating introductions with important contacts in otherwise closed business circles. They can also help qualify opportunities and help their employers avoid the land mines scattered around local markets.

Thesis-based due diligence

With multiples at record levels in the Asia-Pacific region and competition for deals as fierce as ever, the threat of paying too much for assets is plain. But there’s also the risk of offering too little and watching a rival run away with an attractive deal. With quality targets in short supply, making the most of each opportunity is critical to keeping the flywheel spinning profitably. The most successful buyers in this environment find an edge against the competition by ferreting out value others haven’t seen. That lets them bid aggressively but confidently, comfortable that they will be able to create ample value over the asset’s holding period.

Given that the traditional sources of value in the Asia-Pacific market—GDP growth, cheap capital and multiple expansion—won’t provide the same level of support to returns as in years past, due diligence has to focus on other ways to lift a company’s performance. The best funds treat this period of scrutiny as an opportunity to build a clear investment thesis, supported by executable, proprietary insights that will eventually serve as a roadmap for post-acquisition value creation. Most rely on a blend of approaches. We will highlight three of them (see Figure 4.3).

Developing proprietary views on assets. Top-tier firms approach their sweet spot with a proven and familiar investment style that has generated value in the past. This helps sharpen their focus as they look for certain types of companies with familiar characteristics. Every firm is different, but in our experience, the most effective approaches combine elements of several styles:

- Contrarian investing. Finding out-of-favor companies that are due for a cyclical turn or show hidden potential because they have valuable capabilities or assets that have been undermanaged.

- Differentiated value-creation investing. Unlocking value that other firms can’t by tailoring a proven, differentiated value-creation philosophy to companies in familiar industries.

- Macro trend investing. Developing a point of view on the direction of major secular trends and using it to predict secondary or tertiary effects on markets and companies that aren’t yet reflected in prices.

- Cross pollination. Taking themes and investment theses that have worked in one geography or market and applying them systematically to others.

These are not simply generic investment styles. They have been adapted and internalized to become part of the firm’s culture and provide deal teams with a clear set of criteria for analyzing companies before the acquisition. CVC Capital Partners, for instance, uses its value-creation philosophy to assess targets in the several industries it knows most intimately. In 2010, this approach led to a 78% stake in Indonesia’s Matahari Department Store through a $714 million buyout. Many thought CVC had paid too much, but drawing on its deep experience in retail, CVC saw something else: an opportunity to significantly improve performance by expanding the store footprint, adding talent, strengthening a private label program and dialing up promotions. Market share jumped 12 percentage points, and annual revenue growth increased to 13%. As it exited in phases from 2013 to 2016, CVC earned a 7x–8x return on investment.

Combining cost and growth. As the traditional growth-oriented sources of value come under pressure in the Asia-Pacific region, margin expansion is getting a lot more attention. No matter which style of investing a firm chooses, managing costs more aggressively to improve the bottom line is becoming a more critical component of adding value. As we saw in Section 3, however, many firms fall flat when it comes to expanding margins during the hold period. We believe that’s because they fail to take a holistic view of the challenge, starting with the due diligence phase.

What do we mean by holistic? Many PE firms stumble over the challenge of expanding margins because they break their analysis of a company’s potential into two separate areas: opportunities to cut costs and opportunities to increase revenue. The problem is that focusing on either the top line or cost initiatives in isolation can lead to faulty assumptions about how new initiatives will actually affect margins. Looking for cost reductions alone, for instance, might lead to a conclusion that the EBITDA margin could improve by 5% over five years. Yet during the hold period, the investor may discover that capturing a particular revenue opportunity requires significant marketing investment. Or it may turn out that that prices are declining slowly over time. Add it up, and the 5% margin improvement over five years might have been well off target—which, in turn, erodes the firm’s value-creation estimate and threatens the return on investment.

Taking a holistic view of the asset’s potential means looking at cost and growth initiatives together to derive the optimal mix of tactics that will produce the highest level of profitable growth. The most successful firms break it down into a rigorous review of where the company is now and where it needs to be. This involves making sure the firm truly understands the baseline and what current management is trying to accomplish. It can then bring in the right experts to review both top-line and margin-improvement potential. This analysis forms the basis of a high-level transformation plan that prioritizes the few critical initiatives that will make a big difference during ownership. That way, the firm gives itself a head start on value creation from Day 1 after the acquisition.

This kind of analysis helped one firm bid confidently for an Australian specialty retailer that was being sold by another PE firm. Because it was a secondary deal, the buyer’s major concern was that the potential value creation had already been captured by the seller. But by working with advisers and tapping their expertise, the firm was able to quantify significant margin-expansion opportunities that justified the deal. Looking at cost alone might have led to a different conclusion.

Making the most of advanced analytics. The digital age has ushered in new sources of data and sophisticated analytics capabilities that give PE firms unprecedented power to quickly derive insights about target companies’ potential. Customer reviews, geographic information, compensation data, employee and organizational data, social media sentiment and other web data all can be mined for information that sharpens due diligence.

Analytics are no replacement for business judgment or traditional valuation methods. But they can enhance the firm’s understanding of almost any business function. Scraping and analyzing customer reviews from social media websites such as China’s WeChat or Korea’s KakaoTalk can provide valuable insight into product perception and consumer sentiment. Analyzing assortment data can shine a light on relative pricing, product mix and discounting strategies. Mapping a company’s physical locations relative to competitors or target customers can identify white spaces. Tapping career sites such as LinkedIn and Glassdoor can build a better picture of organizational structure and estimated personnel costs. A tangle of spans and layers, for instance, may signal an opportunity to create a more rational, responsive organization.

Reams of raw data could bog down a due diligence effort, but PE firms also have access to valuable tools and can speed analysis. One example is Tableau Software, which allows users to create maps, dashboards and charts to better visualize trends and patterns that would otherwise be invisible. Clarabridge uses text analysis and language processing to analyze customer sentiment, categorize comments and evaluate survey responses. These tools accelerate insight discovery and automate manual due diligence processes. Analysis that used to take months can now be had in hours or days.

Top-tier firms are already deploying analytics to sharpen insights that lead to more confident valuations. When one global fund began its due diligence of an online retailer in India, for instance, it scraped data directly from the web to develop a better understanding of how it might optimize pricing. The data highlighted several opportunities. First, the firm saw that the target company could reshuffle its brands and SKUs to create a more profitable mix. The analysis also revealed several product overlaps and allowed the firm to compare the target’s discounting strategies with those of successful competitors. All of this might have been possible in the past, but it would have required a less precise manual sampling process that would have drained the firm’s time and resources. Analytics delivered insights on a tight timeline and allowed the buyer to confidently assess the opportunity to coax more revenue from the product mix.

Making the most of analytics is hard. It requires significant investment of time and resources. Most of the tools require advanced technical capabilities, which means either hiring staff in-house or working with outside consultants to access and analyze the data. It’s also true that analytics offer no panacea; the insights provided are only as good as the underlying data, and data quality varies widely. What’s clear, however, is that digital tools can significantly deepen a firm’s understanding of a company and its potential. And that can mean the difference between winning a deal at the right price or not.

Proactive value creation

For a number of reasons, the Asia-Pacific region has always presented a particular challenge to PE firms that want to take an active role in value creation. Over the past five years, only about 15% of deals qualified as buyouts, meaning most of the other 85% involved minority stakes. Acceptance of the PE value proposition has grown over the years in the region, but Asia-Pacific business owners still prefer to maintain a tight rein on their companies. This means investors have fewer opportunities to influence real change, and winning buy-in is difficult—something PE firms see as a significant problem. Because the supply of management talent in the region is thin, GPs say that existing company leaders often lack the requisite skills to drive improvement (see Figure 4.4). For years, the region’s headlong growth and margin expansion obscured some of these issues. But as sources of value shift, the ability to engage management in a clear, rigorous value-creation strategy will become an ever-expanding part of creating value and producing returns.

Finding a path to control. None of this is to say that there aren’t plenty of minority deals that succeed in the Asia-Pacific region. After completing a two-stage exit in 2015, Carlyle Group earned a 5x return on a 9% stake in China’s Haier Electronics Group that it had held since 2011. KKR more than doubled its money on an 18% stake in Vietnam-based Masan Consumer that it exited in stages in 2015 and 2016. During the ownership period, KKR was highly involved with management, helping the company unlock its next wave of growth by expanding into new categories and launching an active M&A program.

Taking such an active role in value creation, however, involves some measure of influence over decision making. And increasingly, that means negotiating “path to control” provisions in minority situations. More than three-quarters of the GPs in our survey said they want more control, and most expect a steady increase in such provisions over time (see Figure 4.5).

There are several ways GPs can gain more influence over their investments. Many firms negotiate board seats and the right to veto most major decisions affecting the company. They try to identify change-minded owners early and work with them to formulate a value-creation strategy. Generating buy-in means producing quick wins that demonstrate to the company that the PE value proposition is real. And top-tier firms often bring in globally recognized experts to influence change and produce a “wow” effect.

Defining the right model. For most GPs focused on the Asia-Pacific region, value creation is still a work in progress. Only half say they have a clearly defined model for creating post-acquisition value, and most are still building out their teams and capabilities (see Figure 4.6). GPs also say they are generally successful in putting a robust value-creation plan in place within the first six months of ownership. But they are significantly less effective in seeing it through. A large majority say their plans fall short of intended goals at least 20% of the time.

Because it is hard to replace management teams in the Asia-Pacific region, the most successful firms have developed value-creation models that clearly define how the firm will work with existing management and what support it will provide. Four broad approaches are gaining currency in the region:

- Active value-creation model. Firms like Bain Capital and KKR take an active approach to value creation by building a dedicated team of full-time employees that provides newly acquired portfolio companies with deep strategic analysis, operational support and help in developing a strong value-creation plan. The team is a firmwide resource that works directly with CEOs to engage them in creating a priority list of high-impact initiatives to boost top-line growth and promote margin expansion.

- Maestro model. This model, favored by Carlyle and Temasek Holdings, also focuses on early intervention and continual interaction with top management. But instead of fielding a large, dedicated portfolio group, the firm designates a “maestro”—a senior managing director who works with a small staff and the firm’s deal teams, which interact directly with the CEOs. This group coordinates the efforts of outside experts engaged to help company management teams formulate value-creation plans.

- Adviser-led model. Firms such as EQT prefer a less interventionist approach. Instead of working with every portfolio company, they focus on the companies that need the most attention, helping management teams shape goals and providing the resources to see them through. Often this means drawing on a large network of outside experts who can jump in with specific know-how.

- Playbook model. A playbook lays out a set of strategies, tactics and operational procedures that a firm applies to deal after deal in a given sweet spot. Platinum Equity, for instance, applies a trademarked M&A&O (mergers, acquisitions, operations) turnaround strategy that aims to create value through back-to-basics business strategies combined with operational guidance and resources.

5. Conclusion

What we saw in the Asia-Pacific region over the past year was a PE industry that is maturing rapidly. Instead of getting blown around by global crosswinds, it performed—and performed surprisingly well—according to its own fundamental strengths and weaknesses. GPs paid up for growth in the Internet and technology sectors, but avoided the temptation of putting their ample stock of dry powder to work in expensive sectors with lesser prospects. Returns kept growing and LPs remained cash-positive, indicating that the PE investment cycle is solidly self-sustaining.

But it’s also true that the sources of value in the Asia-Pacific region are shifting. While top-line growth remains the strongest catalyst for value creation, a reliance on GDP and multiple expansion is giving way to a focus on performance improvement and improved margins. Amid fierce competition and record-setting multiples, GPs in the region will need to raise their game to produce market-beating returns. They will have to source more effectively, bring a new level of rigor to due diligence, and develop a value-creation model that can win management buy-in for meaningful performance improvement—even in minority situations.

A key set of questions can help assess where your firm stands on its full-potential journey:

- Has your firm defined a sweet spot with crystal clear criteria for identifying which deals you like and which you don’t?

- Are you confident your firm knows of all the potential opportunities in your chosen markets and sectors?

- Can your firm develop sharp, proprietary insights about the companies it targets?

- Do your sourcing and due diligence capabilities give you a competitive advantage?

- Do you have an established panel of industry advisers and an expert network that you can tap into for sourcing deals and adding value post-acquisition?

- Has your firm developed a repeatable model for creating value in its portfolio companies, with a high degree of buy-in from the deal partners?

Overarching these questions is another one: Has your firm found a way to consistently differentiate itself from a growing horde of competitors through sustained outperformance? While the vibrant economies of the Asia-Pacific region will continue to present private equity investors with real opportunity in the years to come, the capital will flow to those firms that can answer in the affirmative.

Market definition

The Asia-Pacific private equity market as defined for this report

Includes

- Investments and exits with announced values of more than $10 million

- Investments and exits completed in the Asia-Pacific region: Greater China (China, Taiwan and Hong Kong), India, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Southeast Asia (Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Laos, Cambodia, Brunei and Myanmar) and other countries in the region.

- Investments that have closed and those at the agreement-in-principle or definitive agreement stage

Excludes

- Franchise funding, seed and R&D deals

- Any non-PE, non-VC deals (e .g . M&A, consolidations)

- Real estate and infrastructure (e .g . airport, railroad, highway and street construction; heavy construction; ports and containers; and other transport infrastructure)

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Suvir Varma, a Bain & Company partner based in Singapore who leads the firm’s Asia-Pacific Private Equity practice; Kiki Yang, a partner based in Hong Kong who leads Bain’s Greater China Private Equity practice; and a team led by Johanne Dessard, practice area director of Bain’s Private Equity practice.

The authors wish to thank Vinit Bhatia, Michael Thorneman, Weiwen Han, Derek Deng, Sebastien Lamy, Usman Akhtar, Arpan Sheth, Madhur Singhal, Srivatsan Rajan, Wonpyo Choi, Jim Verbeeten and Simon Henderson for their contributions; Rahul Singh for his analytic support and research assistance; and Michael Oneal for his editorial support.

We are grateful to Preqin and the Asian Venture Capital Journal (AVCJ) for the valuable data they provided and for their responsiveness.

This work is based on secondary market research, analysis of financial information available or provided to Bain & Company and a range of interviews with industry participants. Bain & Company has not independently verified any such information provided or available to Bain and makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, that such information is accurate or complete. Projected market and financial information, analyses and conclusions contained herein are based on the information described above and on Bain & Company’s judgment, and should not be construed as definitive forecasts or guarantees of future performance or results. The information and analysis herein does not constitute advice of any kind, is not intended to be used for investment purposes, and neither Bain & Company nor any of its subsidiaries or their respective officers, directors, shareholders, employees or agents accept any responsibility or liability with respect to the use of or reliance on any information or analysis contained in this document. This work is copyright Bain & Company and may not be published, transmitted, broadcast, copied, reproduced or reprinted in whole or in part without the explicit written permission of Bain & Company.