Report

1. Asia-Pacific private equity: Powerful momentum; a changing market

Building on three strong years, the Asia-Pacific private equity (PE) industry achieved its best all-around performance to date in 2017, signaling the start of a new era. Deals were larger, investment was broader and large global investors were more active than ever. All markets in the region rose to new highs, and total deal value reached a record level.

A combination of forces propelled the market to new heights, including an improved macro climate and mounting pressure to invest huge reserves of committed, unspent capital. As the volatility and political shocks of the past two years subsided, stock markets rallied, economic growth took off and PE funds were more comfortable putting capital to work. But, beyond the heady deal making, the market showed signs of maturing and entering a new phase of growth.

Asia-Pacific PE deal value soared to $159 billion in 2017, up 41% over 2016 and 19% higher than the previous all-time high of $133 billion in 2015. Exit value at $115 billion marked the second best year on record, barely below the 2014 peak, and exit activity hit a record high. Fund-raising rose 6% to $66 billion, above the five-year historical average (see Figure 1.1).

Two key forces powered growth in 2017: investors’ growing confidence in the region as macro climate improved, and company owners’ greater overall acceptance of private equity funding. Major players, including global and regional PE firms and institutional investors, were more active in Asia-Pacific last year, accelerating the flow of large deals. Frequently pooling their investments, investors led a surge of megadeals ($1 billion or more) including the region’s largest deal ever—a $14.7 billion buyout of Toshiba Memory Corp. by a group of investors led by Bain Capital and others.1

Company owners are turning in greater numbers to private equity, and they are more willing to cede control—an important transformation that enhances the conditions for the future growth of the industry in the region. The value of buyouts jumped 94% to $72 billion in 2017, making up 45% of total Asia-Pacific deal value, compared with an average of 38% from 2012 to 2016.2 Moreover, Asia-Pacific’s share of global PE assets under management reached a new milestone of 23%, up from 9% a decade ago (see Figure 1.2). Underscoring broadening acceptance of PE, the value of the region’s private equity deals soared to an unprecedented 17% of Asia-Pacific M&A transactions, while public-to-private deals more than doubled to a record $27 billion.

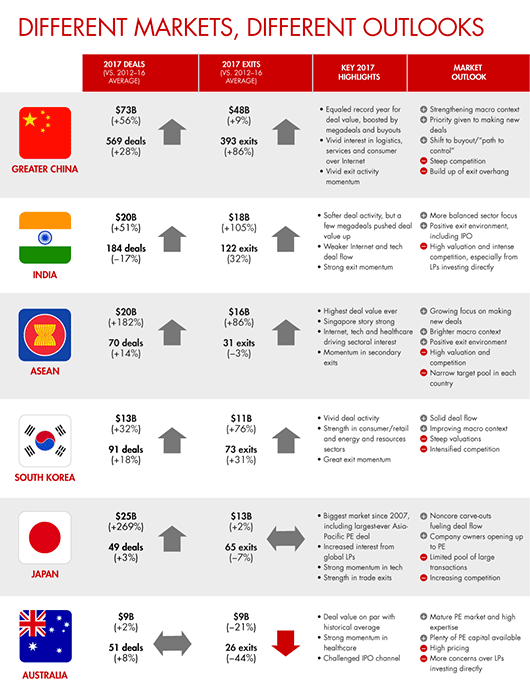

Private equity investments were also more balanced geographically. Though Greater China still accounted for almost half (45%) of the region’s PE activity in 2017, India, Japan and Southeast Asia each represented more than 10% of total deal value. Japan and Southeast Asia saw the biggest gains last year. Investment deal value in Japan rose to $25 billion—up 269% over the average from 2012 to 2016, and Southeast Asia deal value jumped to $20 billion, an increase of 182% over the same five-year average.

Despite large capital calls to support the record level of deal making, limited partners (LPs) remained cash-positive in the first nine months of 2017. For every dollar invested in 2014 to September 2017, the industry already has paid back $1.20. It also continues to generate high returns: The median net internal rate of return (IRR) of Asia-Pacific-focused funds was 11.5%, based on the latest data as of January 2018, up 0.7 percentage points from their performance at the end of 2016. And top-quartile funds are on track to achieve an 18.4% net IRR.

Overall, the Asia-Pacific PE industry has never been healthier. But for fund managers and investors, the region clearly has reached a turning point, with implications for both future investment decisions and portfolio company management. Despite intense competition, steady economic growth may no longer propel multiples. In the Bain 2018 Asia-Pacific private equity survey, GPs said that the top two challenges keeping them awake at night are the lack of attractive deals and the valuations of potential targets being too high. Many believe the market has reached the top of the cycle and prices could decline in 2018. To maintain high returns in a changing environment, GPs will need to help their portfolio companies accelerate organic growth and improve operations. That, in turn, requires new skills and capabilities.

Successful funds are starting to build those capabilities. We see three broad areas of opportunity to develop differentiated growth strategies and improve portfolio companies’ performance:

- Strengthen commercial excellence. Accelerating top-line growth lifts profitability and has a powerful impact on exit multiples, but it’s hard to get right. Only 24% of GPs say they have met top-line expectations in most of their portfolio companies over the last few years, according to our 2018 survey. PE firms that build strength in commercial excellence can help portfolio companies spot organic growth opportunities and introduce initiatives to take advantage of them. Leading GPs are using that approach to improve results and generate big payoffs.

- Rethink strategies for a digital era. Data, analytics and connectivity are rapidly reshaping every sector of the global economy. Top global PE investors are helping management teams understand how new technologies are shifting their profit pools. Digital tools can help them take practical steps to improve their strategic position, commercial performance and cash flow. Portfolio companies that embrace digital strategies are better positioned to manage disruption and keep pace with rapidly changing markets. However, most Asia-Pacific PE funds have work to do. Many say they feel unprepared to help companies navigate a digital shift.

- Make talent a top priority. Our research shows portfolio leadership is the main source of success or failure in value creation for Asia-Pacific private equity investments. However, many PE firms take an overly positive view of management teams early in the investment process. That often leads to surprises during the holding period and a loss of value when companies need to correct course. The most successful PE companies get the right leadership in place to deliver on the value-creation plan. That’s critical to helping portfolio companies outperform.

In Section 2 of this report, we will examine in greater detail how the Asia-Pacific PE industry performed in 2017 and highlight key trends that will shape the PE landscape in the coming years. In Section 3, we will discuss how companies can outperform even as market growth slows, by strengthening commercial excellence, rethinking digital strategies and finding the right talent to fill key roles. We have also included a snapshot review of each market in the region.

Looking back, Asia-Pacific’s private equity industry developed powerful momentum in 2017. Growing investor confidence and increased acceptance of private equity are paving the way for future growth. More important, the winners are already at work raising the performance bar for 2018 and beyond.

2. What happened in 2017?

It was a year of resurgence for Asia-Pacific private equity. After a 16% dip in deal value in 2016, private equity investment came roaring back, setting a new record in 2017. The industry was primed for growth. GPs were sitting on huge stockpiles of capital committed to the region, increasing the pressure to do deals—and the market was flush with large opportunities. Company owners across the region showed a growing appetite for private equity. At the same time, exit activity hit a record high and investors raised the largest Asia-Pacific-focused buyout fund ever. On many fronts, the industry showed signs it is entering a new era—one defined by a broader market, intense competition and shifting sources of value.

Here’s how the year unfolded.

Investments: A new record

Asia-Pacific deal value climbed to an all-time high of $159 billion in 2017, up 41% over 2016 and 19% higher than the historic deal-value peak in 2015 (see Figure 2.1). The number of individual transactions, at 1,015, was down slightly from 2016, but the average deal size rose 47% to $156 million—more than 50% higher than the annual average in 2012 to 2016—and the number of deals valued at $1 billion or more nearly doubled to 27 (see Figure 2.2).

A major force behind that unprecedented growth was the trend toward consortium transactions. Almost two-thirds of deal volume involved multiple investors, about 15 percentage points higher than the previous five-year average. The rise in pooled transactions propelled a surge in megadeals over $1 billion, as GPs, institutional investors and government affiliates vied for attractive targets. Global GPs were particularly active, especially at the top end, participating in 60% of the deal value. They led, or co-led, 71% of the megadeals worth $1 billion or more, including the region’s largest buyout ever—the $14.7 billion acquisition of Toshiba’s semiconductor business by Bain Capital and others (see Figure 2.2).

PE funds’ strong performance over the past four years has riveted LPs’ interest in the region. That, in turn, has generated record levels of dry powder—committed, but unspent capital. At the end of 2017, dry powder in the Asia-Pacific region had risen to $225 billion, or 2.2 years of future supply at the current pace of investment, from $170 billion in 2016 (see Figure 2.3). Venture and growth subasset classes were important components of the increase, and venture dry powder was 90% higher than the annual average during the previous five years. That change is not surprising, given the explosion of venture capital investment and funding over the past decade in China, which now ranks as the world’s second-largest venture capital market, behind only Silicon Valley. India also represents a rapidly growing market for venture and growth deals.

A sharp rise in public-to-private deals also fueled PE investment across the region in 2017. Public-to-private deals made up 17% of total Asia-Pacific deal value, setting a new high. While it’s too early to tell whether this trend will continue, it’s an important signal for the industry, since a rise in public-to-private transactions increases the overall deal pool significantly.

Valuations remain high. Overall, prices in the Asia-Pacific region remained high in 2017. Median PE valuations were just 3% lower than their 2016 record. But, Asia-Pacific’s 2017 average multiple of EBITDA-to-enterprise value for PE transactions fell to 14.1, the first decline since it began a steady march upward in 2013 and spiked sharply in 2016. Still, Asia-Pacific multiples remain much higher than the US average of 10.3.

A broader market. Greater China (China, Hong Kong and Taiwan) continues to attract the most capital—deal value rose 15% to $73 billion in 2017. But strong PE activity spanned all markets, with Japan and Southeast Asia gaining significant market share. Japan’s deal value in 2017 jumped to about $25 billion, up 137% over 2016. Southeast Asia’s market more than doubled to $20 billion, a record high (see Figure 2.4).

Internet and tech still on top. For the third year running, Internet and technology sectors attracted nearly half of deal volume in 2017. Funds’ focus on innovation provided a strong foundation for investment activity, with more than 450 deals in the Internet or technology sectors, and a median size of about $23 million. It also included highly visible deals like SoftBank Capital’s $2.6 billion investment in Flipkart Online Services in India, or the Singapore-based $2.5 billion Grab deal, led by a consortium of investors including Toyota’s Next Technology Fund and SoftBank Capital. Investors also continued to favor consumption-related sectors, including consumer products, retail and healthcare (see Figure 2.5).

Buyouts and control situations—full steam ahead. GPs have long sought to gain more control over their investments in the Asia-Pacific region, and they made big strides in 2017. Buyouts represented 45% of Asia-Pacific deal value in 2017—a record high and about 7 percentage points higher than the average over the previous five years. The region now generates 22% of global buyout value, up from 13% in 2016 (see Figure 2.6). Those numbers also point to company owners’ growing acceptance of PE. Minority deals with a path to control—including board seats or decision rights for most important investments, such as hiring key people or committing to large expense—rose too. Fifty percent of Asia-Pacific companies that were bought with a minority stake in the past two to three years had path-to-control provisions, up from 34% in our 2017 survey.

Many company owners in the region, once skeptical of private equity, are embracing it now as they seek the skills and capabilities to help their businesses grow globally, especially given the accelerating pace of technological changes and slowing growth in some of their home markets. A series of high-profile PE exits in 2017 threw a spotlight on the ability of top-performing GPs to accelerate growth and improve profitability, particularly in countries like India, where the industry has historically struggled to generate a steady stream of good returns. Company owners increasingly understand the industry’s core strengths—robust networks and the ability to analyze trends across industries and markets to develop fresh insights that can guide investment strategies and improve performance. Given the challenge of adapting their business models to rapidly changing digital technologies, it’s not surprising that more company owners are turning to private equity.

Exits: Rebounding higher

Exits rose in all countries across the region, with particularly strong rebounds in Southeast Asia and South Korea. Exit values jumped 25% in 2017, compared with the previous five-year average, to a near record of $115 billion, after declining in 2015 and 2016 (see Figure 2.7). The rebound helped fuel a virtuous industry cycle by returning cash to LPs. Exit activity set a new record with 710 exits, up from the previous peak of 582 in 2015. Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, GIC, rung up the largest exit with the $10.4 billion sale of Global Logistic Properties, setting another record.

Secondary sales (exit to another PE owner) were about 45% higher than the historical average, helping push total exit value to a new high. Trade exits remained solid and were the largest exit channel. IPOs were in line with the historical average.

The value of companies still being held in PE portfolios in June 2017 grew 30% from a year earlier to $424 billion (see Figure 2.8). If multiples begin to contract, PE funds may risk building up an exit overhang. But for now, GPs continued to trim older-vintage companies from their portfolios, reducing the share with a vintage of more than seven years to 26% at the end of 2017, from 29% a year earlier. More than 90% of GPs responding to Bain’s 2018 survey expect strong exit momentum across all channels this year.

Fund-raising: Regional funds bounce back

Fund-raising activity focused exclusively on the Asia-Pacific region was slightly higher than the historical average, with $66 billion raised in 2017. Pan-Asia regional funds expanded their fund-raising activity at the expense of country-focused funds, jumping to 32% of the total from 21% a year earlier, with KKR closing a record $9.3 billion regional buyout fund (see Figure 2.9).

Although Asia-Pacific GPs see competition intensifying and a tougher investment environment, 65% plan to raise funds in the next 24 months.

As we mentioned earlier, Asia-Pacific-focused funds held a record 23% of global private equity assets under management, up sharply from 9% a decade ago.

LPs continued to refocus their relationships with GPs, gravitating to large, experienced funds with strong track records. Reflecting that trend, the total number of funds closing in 2017 was down by about a third, and average fund size grew by almost 65%. The pattern for funds raised in 2017 also underscored LPs’ preference for large funds with proven track records. Only 21% of PE funds on the road last year reached their target in less than 12 months. Large, experienced funds took 14 months on average to close new funds. Smaller, experienced funds were on the road for 16 months, and first-time funds took two years to close (see Figure 2.10).

Returns: Another strong performance

Despite the large capital calls of 2017, LPs remained cash-positive in the first nine months of the year (see Figure 2.11 ). From 2014 to September 2017, LPs received $1.20 for every $1 invested, and the industry continues to generate high returns. Buyout and growth funds had a five-year, end-to-end pooled IRR of 12.5% as of June 2017, nearly 4 percentage points higher than returns from comparable public equities.

Funds focused on the Asia-Pacific region posted a median internal rate of return of 11.5%. Since 2014, the region’s funds have been producing a median IRR of 11% to 12%, and top-quartile funds’ returns were well above most LPs’ expectation of 16% for Asian emerging markets (see Figure 2.12).

The profitability of 2010 and 2011 vintages was solid, and early indications for the 2012 vintage are promising. By contrast, aggregate net returns of recent vintages like 2013 or 2014 were trending lower. However, it’s too early to predict the profitability of younger funds, given that most of these returns are based on theoretical valuation of the owned assets, as opposed to actual selling price.

What’s clear, though, is that strong PE fund performance has increased competition, pushing prices up for now. Finding attractive deals will be more challenging, and GPs will need to work harder to match their returns of the past few years. Results from Bain’s 2018 Asia-Pacific private equity survey show a top concern for many GPs is lower returns, resulting from a lack of attractive deal flow and high valuations.

Changing sources of value

The Asia-Pacific region holds plenty of opportunity for investors to earn strong profits in the coming years. But, the fundamental sources of value creation that investors counted on in the past are changing. To maintain high returns, PE firms will need to develop new capabilities.

With median purchase-price multiples at near-record levels and market growth expected to further slow in the coming years, GPs can no longer expect top-line growth to increase the value of their assets, so they can exit at a premium. More than 70% of Asia-Pacific GPs say competition increased in 2017, especially from regional and local PE firms, making it more difficult to find attractive deals. A majority say the lack of attractive deal opportunities for 2018 is one of the top two challenges that keep them awake at night. They also see a clear decline in proprietary deals (see Figures 2.13 and 2.14).

Until now, most PE funds investing in the region have been content to ride the wave of strong macro growth and expanding multiples—buying high and selling higher. Already, these external factors have become far less important as sources of returns than they were five years ago. Going forward, the most important factors will be internal—top-line growth, increasing margins and strategic M&A (see Figure 2.15). Anticipating that change, successful GPs already have begun to play a more active role helping their portfolio companies create value by accelerating organic growth, improving capital efficiency, reducing cost and pursuing strategic mergers and acquisitions.

For many, however, this fundamental shift in approach will require adding new capabilities. As we detail in the coming pages, a few key strategies can prepare Asia-Pacific PE firms to ride the new wave of value creation and produce top-tier returns: help portfolio companies build commercial excellence, make the most of digital technologies and excel at talent management.

The Asia-Pacific PE industry has reached a critical turning point, and investors in the region face new challenges and opportunities. Some GPs believe the market has reached the top of the cycle, and many are concerned that multiples could decline. Whether the cycle turns down in 2018 or later, the days of heady emerging-market growth are probably over. PE funds that start building the skills and expertise to create internal sources of value will have the tools to help them deliver strong returns and attract fresh capital for a new era.

Infographic: Private Equity in Asia-Pacific

3. Creating value in an evolving market

It’s becoming tougher to deliver big gains from private equity investments in the Asia-Pacific region. Competition is more intense, valuations are soaring and the sources of value are shifting. That means GPs need to rethink how they evaluate and seize new opportunities. Those who deliver profitable organic growth, and do it quickly, can prosper even in a challenging market.

Three key capabilities can help PE firms take a more active role accelerating top-line growth: building commercial excellence, harnessing digital technologies and improving talent management. Leading PE firms already have begun embracing a more active management approach. We describe some of their experiences in the three sections that follow, highlighting their impressive results.

...

Building commercial excellence

Increasing top-line growth has the biggest impact on exit multiples. GPs who spot growth opportunities early can bid for companies more confidently, generate more value post-acquisition and exit more profitably. In our experience, building commercial excellence is a deep, mostly untapped source of growth. We define commercial excellence as a set of capabilities that can generate growth including customer segmentation, salesforce effectiveness, category management and pricing. PE firms that help their portfolio companies improve their go-to-market approach generate triple benefits: top-line acceleration, margin expansion and higher exit multiples.

Improving commercial operations often produces a quick win. Advanced analytics can rapidly help sales teams shift to winning behaviors, for example. When companies in a B2B setting launch multiple commercial excellence initiatives, we typically see 10% to 20% top-line acceleration, and a 10% to 15% EBITDA uptick—and even more when they harness digital technologies. Our research also shows that median return on investment is 20% to 30% higher when using a commercial acceleration program (see Figure 3.1).

Take the example of a global IT infrastructure company acquired by a US-based PE firm. The GP leadership team quickly realized that the IT company’s biggest growth opportunity was in China, but it was not in a position of strength: A key competitor dominated the most important distributor-led sales channel.

The PE team helped management review its China operations using a systematic assessment of its market position based on customer, supplier and distributor input. This outside-in view allowed the management team to identify major distribution concerns, including poor incentives and insufficient market coverage. It also quickly revealed a weak presence in smaller Chinese cities compared with the competition.

To address those problems, the company significantly upgraded its channel engagement, using more distributors to accelerate sales. At the same time, the leadership team launched several initiatives aimed at quick wins. To increase sales, for example, it redesigned the conditional rebate to incentivize both wholesalers and its own frontline staff. It also deployed a methodical approach to screen and select new distributors for areas where coverage was low.

The results were impressive: The company’s sales took off, and in six months the leadership team had hit its 12-month target with a growth rate 2.25 times higher than that of the market. In the meantime, the distributor coverage increased by 60% (see Figure 3.2).

Building new muscles

Top-line growth has a multiplier effect on creating value because it lifts profit along with revenue. That generates impressive momentum, making it easier to exit at a high multiple. Yet few PE firms do it well—including those focused on the Asia-Pacific region. Our 2018 survey indicates only 24% achieved their top-line goals in most of their portfolio companies.

One explanation is that historically, Asia-Pacific PE firms could surf on market growth and take advantage of expanding multiples to underwrite future value projections. Now, with macro conditions slowing and the looming risk of contracting multiples, many recognize they need new muscles to help portfolio companies accelerate organic growth. Bain research shows that portfolio companies that grew by gaining market share or investing in businesses adjacent to their core produced returns 30% to 50% higher than those that relied on market growth alone. However, 56% of the region’s funds do not feel fully confident to underwrite the top-line and bottom-line opportunities after due diligence, and 68% are not prepared to make the most of commercial excellence initiatives involving the salesforce, pricing or product offering after the acquisition (see Figure 3.3).

Implementing commercial excellence initiatives is hard work. Customer segmentation, pricing, salesforce models and product offerings are interlinked, making it complex to set change in motion. Upgrading a company’s go-to-market model requires a change in mindset. Many companies lack vital market data, such as their share of customers’ wallet, which is the starting point for overhauling strategy. And for many GPs, commercial acceleration seems a risky and time-consuming endeavor.

But digital innovation has made inaction a bigger risk. Digital technologies are revolutionizing the way companies identify, understand and serve customers. New entrants and the most agile incumbents are rapidly exploiting technologies such as customer and pricing analytics to transform their commercial capabilities. Big Data has dramatically improved the precision of market and customer-segmentation efforts as firms tap into large streams of transactions, advanced analytics, social media activity and other windows on customer behavior.

PE firms that underestimate a company’s exposure to disruption in these areas can see value evaporate rapidly. But there’s an upside too: Diagnosing opportunities to improve commercial capabilities can produce step changes in top- and bottom-line performance by allowing companies to open new markets and generate more sales with increased efficiency.

This was precisely the approach that Carver Korea, a leading Korean cosmetics brand, and its PE owners used to multiply its value 4.5 times within 15 months. The company had tripled its top-line growth every year from 2012 to 2015 before selling a 60% stake to Bain Capital and Goldman Sachs in 2016 (see Figure 3.2). In order to sustain the momentum, the investors and management had to redefine Carver Korea’s growth strategy and quickly transform the business.

Four key initiatives fueled the spectacular rise in value. The company overhauled customer segmentation, expanding its loyal customer base while targeting a new segment—younger cosmetics customers—with an online pilot program. It sharpened its “Aesthetic” brand identity and eliminated inconsistent messages. It also simplified its product lines, eliminating underperforming product models. Finally, the company lowered its channel risk by expanding online, in drugstores and duty-free shops, and improving exports to China. To ensure those changes would stick, owners and management agreed to a major organizational change, moving from the one-man founder organization to a functional structure led by expert teams.

Private Equity in Asia-Pacific 2018

A look at the private equity highlights in the region from last year and the outlook for 2018 and beyond.

Starting early in diligence

Because it can take time for commercial acceleration efforts to bear fruit, the most effective PE funds start early—most often in due diligence—so they can launch a full set of initiatives right after acquisition. The firms most adept at sorting through these issues have developed a diagnostic capability that they can use repeatedly during due diligence to evaluate a company’s upside. That diagnostic then suggests which initiatives will help the company reach its goals and what tools or technologies will help accelerate results. Gathering that information prior to the sale gives GPs a valuable jump-start after the acquisition.

As one PE fund conducted due diligence on a China-based IT company, the big question was whether it would be able to achieve the margins of its competitors in India. An analysis of the profit profile of the two countries highlighted structural differences that were unlikely to change under PE ownership, but it also pointed to two main areas where the company could improve its margins—pricing and sales productivity, which was far lower than the competition. New initiatives to improve profits showed the company could boost its EBITDA by 3 to 4 percentage points, or more, depending on execution. That analysis gave the PE fund added confidence to pitch and a plan to quickly start improving the company’s performance.

Agility and rigor after the acquisition

Leading PE funds improve commercial excellence in sprints as soon as the deal closes. They quickly review customer segmentation based on the potential and lifetime value of current and new accounts, as opposed to their value today. Next, they identify growth opportunities and quick wins, and set new initiatives in motion.

A well-designed commercial acceleration plan can power a major financial turnaround. Swisse Wellness, a leading Australian vitamin and health-products company, reversed a cash-flow shortfall and raised its EBITDA by 75 times in two years, thanks to a commercial excellence program designed together with investor Goldman Sachs (see Figure 3.2).

By 2012, Swisse’s attempt to enter the US market had begun to strain cash flow. The company received a A$70 million capital injection from Goldman Sachs Special Situations Group in 2013 to help it return to profitable growth. Swisse started to implement rigorous cost-reduction and profit-improvement programs, as well as commercial acceleration initiatives to build a strong foundation for longer-term growth. The effort overhauled Swisse’s pricing and promotion strategy, which had been cannibalizing the market’s profit pool. It put in place a more disciplined promotion strategy, harnessed data science to track the effectiveness of its promotions and created a more structured marketing calendar. The new approach helped push industry prices up and increase margins.

At the same time, it turned to China to turbocharge growth. Building on the powerful equity of Australia-branded products and China’s growing interest in health trends, Swisse triggered a wave of Chinese demand for Australian consumer products. Improving its supply chain muscle, it strengthened its network of contract manufacturers and secured contracts with key suppliers. It also managed a complex demand scenario, designing a new cross-border pricing strategy and a more systematic go-to-market approach. When Goldman Sachs exited in September 2015, selling to Biostime in a deal that valued the company at A$1.7 billion, Swisse had an EBITDA close to A$150 million, up from A$2 million in 2013.

Companies that continually identify new customer groups, understand their preferences and serve them better have always excelled. But as digital technologies rapidly transform industries and markets, the risk of being outmaneuvered by savvier competitors is growing. PE companies that develop commercial excellence as a core capability will help their portfolio companies stay ahead of the market-disruption curve, grow faster and deliver top returns.

...

Making the most of digital technologies

Big Data, analytics and connectivity are accelerating change in every sector of the global economy. As these technologies reshape industries, companies face a growing risk of digital disruption. Leading PE funds are turning these trends to their advantage, by using advanced analytics tools and capabilities to seize new opportunities and lead change. Digital competence enhances a fund’s ability to assess companies during diligence and improve their performance during the period they are held, creating a significant competitive advantage.

To date, only a few investors have figured out how to take advantage of new technologies. Our research shows fewer than 5% of Asia-Pacific GPs believe they are fully prepared to help their portfolio companies manage digital disruption. Many have begun building new capabilities, but about 30% say they have a long way to go to develop the added competence needed for due diligence or post-acquisition, and almost 60% claim they don’t have a digital X-ray tool to identify where to focus in the portfolio (see Figure 3.4).

For private equity funds, the best way to look at the digital risks and opportunities is through the classic PE investment lens: How can I increase cash flow over the next three to five years, and how can I increase the company’s franchise value at exit? Many managers view the digital challenge as confusing or overwhelming. Bain’s approach is to focus on the business problems that technology is solving in each industry. That allows companies to quickly identify the digital actions that matter most.

The level of disruption differs for each industry and company, and is constantly evolving. To assess the risks and opportunities for a given company, leading PE firms start with a few important questions: Is digital expanding or reducing the profit pool for a target company’s industry, and how does the impact vary from one industry segment to another? The speed of change is also important. Will the goalposts for success change within the next 12 months or the next five years? What could the target company do to develop new opportunities and reduce the risk? Finally, what impact would those moves have on deal return? The answers will vary widely, depending on the company.

Supercharged growth

Our experience shows that when PE investors help portfolio companies align digital transformation programs with strategy, they can deliver big wins. Courts Asia, a Southeast Asian retailer, is a striking example. When Baring Private Equity Asia acquired a majority stake in Courts in 2007, it was a loss-making brick-and-mortar retailer. The retailer had an overextended store network and poor customer feedback, and it sold few products online. In 2010, Courts and PE partner Baring developed an omnichannel strategy that supercharged its growth as part of a broader transformation. When they launched an IPO in October 2012, Courts had a leading position in its markets, the value of Baring’s stake had more than doubled and the IPO was heavily oversubscribed.

Courts’s first step was a rapid turnaround program that restructured its store footprint, cut costs and improved salesforce effectiveness. As the company turned profitable, Baring and Courts focused on accelerating growth and delighting customers. Both saw an opportunity for the company to pioneer omnichannel retailing in Southeast Asia. Management set to work building a leading position in online retailing and developing new ways to enhance customer loyalty, including a one-stop mobile shop. Finally, it developed touch points to gather continual feedback from customers and deepen its relationship with them through targeted promotions. By 2014, Courts ranked first among traditional retailers based on website traffic in Singapore, and in 2016, an online poll named it the best home and electronics retailer in Asia.

Courts’s growth story underscores how digital tools can help companies identify new opportunities and make the most of them. China’s Qingdao Haier, a global household electrical appliances company, provides another example. KKR acquired a 10% stake in Haier in September 2013, becoming its strategic partner. At that point, Haier suffered from slowing growth in white goods, a weak position in brown goods and a shrinking market share. Working together, the two companies determined that Haier could increase its sales by putting Big Data at the core of its marketing strategy. When KKR sold part of its stake four years later, Haier’s stock price had almost tripled and the company had won several prestigious industry awards.

Haier had already begun reshaping its business model for a digital economy before KKR invested, and was betting on a new online strategy to position the company for long-term growth. KKR worked closely with Haier to develop a digital sales and marketing strategy that used Big Data to better understand customers’ needs and preferences such as reducing costs, improving security or seeking out leisure opportunities. That helped the company identify the right categories of products and services to offer. The goal was to use data to create a win-win marketing ecosystem powered by user interactions.

Initially, Haier created a few pilot initiatives in priority areas, including a heat map of potential consumer spending and profiles. Sharing the map with the front line helped the company run more targeted marketing campaigns. Despite its distributor-led business model, Haier developed powerful tools to connect with end customers, monitoring each interaction between distributor sales representative and customers. Haier used a cloud platform to analyze millions of data messages about their equipment every day and wielded Big Data and artificial intelligence to optimize products and improve customers’ experience. Ultimately, the digital strategy helped Haier shift from a technology-focused mindset to a customer-centric company, giving it more resilience to adapt to a fast-changing market.

Today forward, future back

Companies trying to develop a digital strategy need to do two things well: improve existing products or services and anticipate how technological advances may revolutionize them in the future. For some management teams, this dual approach may feel overwhelming. In reality, the leadership teams at most companies have a reasonably good idea about where their industry is headed in the next 10 years or so. For example, retailers know that first-generation e-commerce is being replaced by increasingly sophisticated omnichannel offerings. Auto suppliers are watching the development of autonomous and electric vehicles and can anticipate how they will change the market in the coming decade.

The problem for many companies is that they set in motion too many digital initiatives, not too few. PE firms face the same challenge: choosing the right strategy for portfolio companies amid market turbulence and rapid change. Industry-specific analysis can help investors narrow the focus and create a pragmatic plan to improve short-term performance while moving toward longer-term goals.

The most pragmatic approach is to look at each target company’s business from two perspectives: What are the risks and opportunities today, and what will they be in 10 years? We call this dual view today forward, future back (see Figure 3.5).

Starting with today forward, leadership teams need to assess how digital technology already is affecting their profit pool and how the company should respond. That involves using digital X-ray tools to diagnose a company’s strengths or weaknesses. Using those insights, leadership teams can develop initiatives that will produce a big leap in performance over the next three to five years.

Future back comes from the other direction. It means envisioning how technology is likely to transform the profit pool over the longer term. With that perspective, companies can start preparing for long-term change concurrently.

Of course, shaping a digital strategy that responds to those questions is just the beginning. To keep pace with innovation, PE funds must continue to review digital opportunities and risk throughout the investment cycle, from due diligence through exit.

Balancing current and future strategies

PE investors are generally focused on creating value over the next three to five years, so their primary focus in both diligence and ownership is today forward, or what can they do now to generate EBITDA and improve top-line growth. That said, investors can profit from the future-back perspective for two very practical reasons. First, a thorough, fact-based analysis of what’s knowable about the future is the best defense against paying too much for an asset or getting blindsided later. Second, a firm grasp of what’s coming provides the foundation for the most effective value-creation plan. It gives direction to the short-term initiatives and helps the fund build the most compelling exit story.

Today-forward and future-back analysis helped generate early substantial gains at a slow-growing Asia-based digital company purchased by a group of global PE funds. The future growth prospects looked strong as the deal closed. The company was operating in a market with double-digit growth, and it had nascent but promising relationships with a set of large customers. But the business was burning cash at a rapid clip, and competition was flooding into the market.

Together with its new PE owners, the company revamped its strategy. It repositioned its service offering around select businesses likely to benefit from digital shifts. That helped clarify brand positioning. Changes to the sales team culture and the operating model helped the company better identify opportunities with clients and prospects, and directed frontline staff to the most important opportunities. Finally, it shifted global resources, doubling down in some areas and pulling back in others.

Less than 18 months later, sales had grown by seven times and the company was nearly profitable. The digital strategy had improved its annual contribution margin by 10 percentage points, and the share of repeat clients had grown 60 to 70 percentage points (see Figure 3.6). The turnaround was a major win from a today-forward standpoint. But it also incorporated a future-back gain. The company’s new focus on speed, agility and the most promising future markets made it more resilient in a fast-changing market.

Make the most of digital during due diligence

Striking the right balance between today-forward initiatives and future-back priorities is difficult, but it is critical to have both in hand early to avoid being blindsided later. Leading companies start using digital tools during due diligence to glean better insights about future growth opportunities and risks.

As one global PE investor considered acquiring a stake in an Indian fashion manufacturer, a key question centered on market growth and the company’s ability to win market share. To create value, the company needed to progressively shift its sales online. But it was starting from scratch: brick-and-mortar retailers made up almost all of its revenue, and management had no plan for a radical shift to online sales.

Advanced web-scraping analysis of leading e-commerce platforms highlighted why the company’s online positioning lagged the competition. Its discounting policy was not competitive, the price range for the products offered online was extremely limited, the company was difficult to find on the web, and it did not have the leadership or platform partnerships to differentiate its online presence.

Using global industry benchmarks and an extensive customer survey, the fund determined that the company had the potential to multiply its online revenue by 20 to 50 times during a typical PE ownership cycle. The deal team also realized that the company could develop its own e-commerce capabilities, adding to the potential upside. The PE company’s analysis ultimately allowed it to formulate a bid that matched the company’s potential, and to begin work quickly on a set of high-priority initiatives using digital technologies to create value.

A stepping-stone approach

The most effective value-creation plans identify a clear objective on the horizon and aim the company in that direction by laying out a set of practical initiatives that can create progress in the short term. These are steppingstones, or concrete measures that generate EBITDA now while bringing the company closer to its objective over the next couple of years.

One Asian agribusiness company majority owned by an institutional investor developed a digital strategy aimed at increasing returns by 10% within three years (see Figure 3.6). The leadership team wanted to get ahead of competitors who were starting to use digital tools to transform their businesses. As they designed a comprehensive digital roadmap, however, they realized the company did not have adequate resources to launch all the initiatives at once.

Rethinking its approach, the team assessed digital challenges in the industry through a double lens—today forward and future back. They gathered input from internal stakeholders, suppliers, clients and a cross-functional team. From a long list of possible initiatives, management placed a few big bets that could both create significant value and help the company’s products stand out in the market.

The first stepping-stone was an e-commerce platform to help the company access smaller customers, reduce marketing inefficiencies and create greater customer loyalty. In a rapid 12-week sprint, the company collected input from customers and staff, designed a working prototype of the platform and identified potential vendors. Quickly, a number of small customers registered on the pilot platform and generated multiple transactions. Those results were promising enough for the company to decide to roll it out to the entire organization.

Making products in their supply chain more traceable—a critical capability in agribusiness—was a second important stepping-stone. A prototype digital tool helped management identify both farmers and their products and increased the visibility of stock in the warehouse. That generated new business opportunities, giving the company a strong advantage selling to customers who demand a high degree of traceability. It also allowed the company to reward farmers based on the quality of their products.

The company’s digital strategy and game-changing initiatives helped it quickly take a digital lead, improve its margins and accelerate sales. The pilot initiatives are on track to increase profits by 10% over three years, based on lower costs, increased margins and higher output.

Diagnosing strengths and weakness across the portfolio

Many PE funds are also understandably concerned about assessing the digital readiness of the assets they already own. Performing a digital diagnostic across the portfolio can be an effective way to identify which initiatives will produce the most value.

A portfolio scan should identify the most important sources of digital disruption facing each company and assess how ready it is to compete in a changed market. We find it useful to score sectors on a digital disruption index, which tracks how digital technology is affecting key aspects of doing business in that industry—products and services, customer and channel engagement, operations and new business models (see Figure 3.7). It’s then possible to rank companies according to how thoroughly they have kept pace with these changes and to what degree they are deploying technology across the value chain.

The most effective scans engage the leadership of portfolio companies, to help determine how much digital technology has seeped into the organization’s DNA. The assessment looks at the company’s digital systems and infrastructure, its technology stack, its fluency in analytics and the management systems in place supporting digital transformation. It aims to measure the quality of activity, not the quantity. Most companies are brimming with digital initiatives, but fewer are able to sort and prioritize them based on their potential impact.

PE funds can use a digital scan to benchmark portfolio companies against their competition and begin to assign value to initiatives that close readiness gaps or exploit strengths. This process will also identify sources of weakness or strength across the portfolio, such as opportunities to create a digital marketing center of expertise or effective ways to share best practices in supply chain transparency. The objective is to shine a light on which two or three initiatives deserve the firm’s immediate attention so its leadership can marshal the resources to accelerate those projects. Ultimately, PE funds can make digital benchmarking a standard process at relevant portfolio companies. Having access to industry-specific digital developments on an ongoing basis, through the right partnerships, gives GPs a handy radar for potential disruption.

Create a digital ecosystem

Top-performing PE firms recognize the importance of building digital capabilities. But few believe that having in-house digital experts would help them make smarter investment decisions. The reason is clear: It’s hard for individual experts to possess the breadth of industry-specific knowledge required to generate effective insights. In our experience, firms are better off building an ecosystem of capabilities to support the digital needs and analytic ambitions of their portfolio companies. An ecosystem could include the following elements.

- A network of IT providers, advanced analytics vendors or digital partners, sector by sector, to be a resource of digital support for portfolio companies.

- Centers of excellence within the firm that give portfolio companies access to proven solutions or best practices in areas like digital marketing or social media.

- Connections to outside thinkers with expertise in technologies or industries with special importance to the firm. This pool could provide perspectives on digital trends and what they mean for the portfolio companies.

- An internal team to manage the ecosystem and oversee initiatives for the entire portfolio. This group should be available to help the fund’s investors better understand major technology trends and how they affect the industries in the portfolio.

Over the last three decades, private equity firms have helped portfolio companies build the management skills to deal with sweeping changes to the business landscape, including globalization and e-commerce. Digital innovation, like those previous business challenges, presents another opportunity for the PE industry to lead in shaping new strategies for shifting markets.

...

Managing talent

PE firms often spend a lot of time searching for the right company in the right sector, but finding talented leaders is just as important to performance. Bain research shows that leadership problems in portfolio companies are common throughout the Asia-Pacific region and have substantial impact on value creation.

According to our 2018 survey, talent is the most important factor behind deal success and failure in the Asia-Pacific PE market, based on recent exits. But putting the right leaders in place is difficult: 70% of GPs told us they struggle with organizational challenges in a majority of their portfolio companies (see Figure 3.8). Few GPs in the region feel fully capable of assessing and managing the leadership team of their portfolio companies.

Because market growth has propelled Asia-Pacific PE multiples until recently, GPs focused on the region traditionally have not devoted a lot of energy to talent management. That is one reason few Asia-Pacific GPs feel they have the skills to do it well. But with market growth slowing, managing talent has become essential. As PE firms turn their focus to improving operations to create value, their portfolio companies will need different leadership skills to meet their performance targets. That means GPs will need new capabilities to assess top talent and build out their teams faster.

Finding talent that can deliver on the investment plan is critical, especially when the deal thesis requires a fundamental shift in strategy or operating model. Yet, in our experience, PE firms often neglect to make important talent decisions early on, both in the C-suite and in other mission-critical roles.

Asia-Pacific GPs in particular struggle to identify the right talent for the right job. One reason is that founding families are still involved in running many companies, making leadership change tricky. Minority-stake deals have also limited the ability for PE funds to influence people decisions. Although in 2017, buyouts were the first subasset class by far in value, 85% of Asia-Pacific deals over the past five years were minority-stake deals. Third, and not specific to this part of the world, PE funds may find their access to management limited prior to the announcement of a sale, especially when there is no exclusivity. Also, soon after closing the deal, GPs often go through a honeymoon period in which they tend to avoid tough issues, including those involving leadership. Finally, management assessment is an art, not a science, and all companies struggle to get it right, including PE firms.

Match talent to the value-creation roadmap

Of course, the definition of good leadership differs from company to company. The golden rule for PE funds is identifying the capabilities required to deliver on the investment thesis and value-creation plan. The leadership qualities that worked in the past won’t necessarily work in the future. Strategy frequently shifts under PE ownership and so do the capabilities required for success. If the investment thesis depends on pursing mergers and acquisitions, for example, the leadership team will need individuals with business development expertise and financial acumen.

GPs should be able to identify the critical management capabilities for success during due diligence—well before the company has fully shaped a new strategy. When the GP of one global PE firm assessed an oil and gas company in Asia, management quality was a big question mark. Some members of the leadership team had departed after a larger firm acquired the target company’s parent, and the quality of the remaining team was unclear. Using new data sources and web scraping of sites like LinkedIn and Glassdoor, the GP analyzed management turnover and the strengths of its remaining leadership team. The data showed the company was better positioned than most of its competitors on these two fronts. Further analysis and interviews confirmed that the company had lost few of its most talented managers. That gave the PE fund confidence that the current management team could implement the value-creation plan.

Start at the top

When assessing portfolio company teams, it’s important to begin at the top and focus on the mission-critical roles. The CEO should have the right profile to lead the planned changes. Top executives have differing strengths and may excel as commercial executors, financial value drivers or corporate entrepreneurs. The value-creation plan determines what kind of bench strength the company needs.

Of course, the CEO should to be able to work well with private equity partners and understand their focus on delivering returns within a given time frame. The most effective portfolio company CEOs strike a good balance between short- and long-term goals that will lead to the deal’s success. They appreciate the analytical perspective that PE funds bring and are ready to depart from “business as usual,” to improve performance.

The next step is making sure the entire C-suite is aligned to the company’s new mission and strategy. A top CEO may bring A-level talent with him or her. But C-suite roles should align with the company’s new mission and strategy. Leading PE firms define the leadership roles and help determine who fills them. That might involve creating C-suite positions that didn’t exist before or eliminating others. It may also require rescoping or reshaping roles to focus on new imperatives.

Getting talent right doesn’t stop at the C-suite. One important mistake many GPs make is to overlook the roles further down the organization that are central to the deal’s success. These are typically complex roles fundamental to value creation—and roles where outperformance is key to success. Mission-critical roles tend to involve a high degree of ambiguity and trade-offs. They require quick thinking and the ability to make decisions that will directly affect the company’s performance against its plan.

Leading GPs identify these roles and make it a priority to fill them with top talent. These roles typically include sensitive frontline interactions and customer negotiations that can have a major effect on the company’s business. A PE firm helping an apparel company expand into a new region, for example, will need to hire top-notch talent in that channel. Even middle managers can make the difference between success and failure.

Assessing talent

A few leading PE funds in this region are developing best practices for assessing talent. According to Bain’s 2018 Asia-Pacific private equity survey, most firms are still developing leadership-assessment capabilities, with 84% claiming they do not have a chief of talent to do this. And about 60% recognize they don’t have a fully functioning process to assess the management team during due diligence or after the acquisition (see Figure 3.9).

Some PE firms are closing the gap by hiring global or regional talent directors that can help evaluate target company teams and strengthen portfolio company leadership. They can canvass external candidates and fill key roles quickly, and may look outside the region or industry, if necessary.

In Asia-Pacific, GPs also mine adviser networks for talent. They build these networks throughout the investment value chain, from deal sourcing and due diligence through the ownership period. Advisers may take on value-creation roles, including board seats or more direct management roles.

More broadly, we also see data-based assessment and human-development specialist firms emerging in more mature private equity markets. These companies are using data and analytics to enhance the accuracy and effectiveness of predicting how well current leaders and future recruits will deliver against an investment thesis.

Choosing the best management talent for a portfolio company is not a one-time drill. As a company’s strategy evolves, staffing and assessment priorities will shift as well. Top PE firms perform regular check-ins to ensure that the right team is in place and performing well. They also continue to refine their criteria for what great looks like, based on how the company is evolving.

Asia-Pacific GPs that build stronger talent management capabilities will be better positioned to produce top returns as the sources of value for PE performance in the region shift.

4. Conclusion

The Asia-Pacific PE market crossed several key milestones in 2017: the highest deal value ever, peak exit activity, the largest Asia-Pacific-focused PE fund ever and a record share of the global buyout market. Four years of successful investment cycles and positive cash flow have given investors confidence in the strength and reliability of the market. Those changes signal a maturing market and the start of a new era—one in which private equity is of increasing importance to the region’s economy.

However, PE funds focused on the region face several new challenges, including an accelerating shift in the sources of value. To continue producing solid returns, GPs will need to add new capabilities. Digital competence, commercial excellence and talent assessment are some of the critical skills that winning funds already have started to develop. Four questions can help GPs assess whether they are positioned to win in a changing market, and where they may still need to build muscle.

- Have you begun to take advantage of shifting sources of profits in the private equity market, including greater emphasis on organic growth?

- Do you analyze and recommend changes to portfolio companies’ go-to-market model?

- Does your fund have a repeatable model to help portfolio companies make the most of digital technologies?

- How robust is your firm’s assessment of management talent at target and portfolio companies?

The pace of change for most industries will be rapid in 2018 and beyond, as companies grapple with ongoing technological shifts and market disruption. But that setting also creates new opportunities for GPs to distinguish themselves from the competition and deliver superior returns. Those who help their portfolio companies develop new sources of value will be tomorrow’s leaders.

Market definition

The Asia-Pacific private equity market as defined for this report

Includes

- Investments and exits with announced values of more than $10 million

- Investments and exits completed in the Asia-Pacific region: Greater China (China, Taiwan and Hong Kong), India, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Southeast Asia (Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Laos, Cambodia, Brunei and Myanmar) and other countries in the region

- Investments that have closed and those at the agreement-in-principle or definitive agreement stage

Excludes

- Franchise funding, seed and R&D deals

- Any non-PE, non-VC deals (e.g., M&A, consolidations)

- Real estate and infrastructure (e.g., airport, railroad, highway and street construction; heavy construction; ports and containers; and other transport infrastructure)

1 The total value of the transaction, which is under regulatory review, was $17.9 billion, with private equity investors contributing $14.7 billion.

2 Total buyout value for the Asia-Pacific region was $83 billion if the calculations also included add-on deals, which involve assets that are then added to existing platform companies.

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Suvir Varma, a Bain & Company partner based in Singapore and senior member of Bain’s Private Equity practice; Lalit Reddy, a partner based in Bangalore and a member of Bain’s India Private Equity practice; and a team led by Johanne Dessard, a practice director in Bain’s Private Equity practice.

The authors wish to thank Kiki Yang, Vinit Bhatia, Michael Thorneman, Weiwen Han, Sebastien Lamy, Usman Akhtar, Arpan Sheth, Wonpyo Choi, Jim Verbeeten, James Viles and Raymond Hass for their contributions; Rahul Singh, Sindhu Nair and Pallavi Singh for their analytic support and research assistance; and Gail Edmondson for her editorial support.

This work is based on secondary market research, analysis of financial information available or provided to Bain & Company and a range of interviews with industry participants. Bain & Company has not independently verified any such information provided or available to Bain and makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, that such information is accurate or complete. Projected market and financial information, analyses and conclusions contained herein are based on the information described above and on Bain & Company’s judgment, and should not be construed as definitive forecasts or guarantees of future performance or results. The information and analysis herein does not constitute advice of any kind, is not intended to be used for investment purposes, and neither Bain & Company nor any of its subsidiaries or their respective officers, directors, shareholders, employees or agents accept any responsibility or liability with respect to the use of or reliance on any information or analysis contained in this document. Bain & Company does not endorse, and nothing herein should be construed as a recommendation to invest in, any fund described in this report. This work is copyright Bain & Company and may not be published, transmitted, broadcast, copied, reproduced or reprinted in whole or in part without the explicit written permission of Bain & Company.

We are grateful to Preqin and the Asian Venture Capital Journal (AVCJ) for the valuable data they provided and for their responsiveness.