Forbes.com

Too many organizations fail to make and execute critical decisions well. Often it’s because their decision processes are deeply flawed.

Here’s a pretty typical scenario. A day before the key meeting, attendees get copies of a 165-page PowerPoint presentation. The presentation outlines the principal recommendation, the logic behind it and the supporting data.

Nobody reads all that, of course, because they assume someone will walk them through it at the meeting. And indeed, someone does. But then comes trouble. Some people believe the team has looked at the wrong data. Others question the criteria underlying the recommendation. Still others wonder whether there’s a better alternative. One executive declares, “We could never actually implement that recommendation.”

Stymied, everyone agrees to delay the decision until the following month.

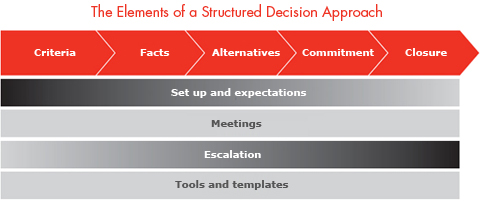

The scenario would be funny if it weren’t so painful: We have seen many organizations struggle with just such dysfunctional processes. But companies that are most effective at decisions don’t get bogged down like this. They follow a carefully structured approach to decisions, one that ensures agreement on criteria, facts, alternatives, commitment and closure (see figure below). Let’s examine each element in turn.

Criteria. You can’t come to a decision unless you know the criteria for making it. A major UK retailer, for instance, launched an experimental program of always matching competitors’ prices. But when the test results arrived, executives were baffled. They had never determined whether the test’s goal was to increase store profits, increase market share, build customer loyalty or something else entirely. They had no criteria for evaluating success or failure, so they couldn’t decide whether to terminate the program or roll it out nationally.

Facts. Twenty years ago, gathering data required a lot of time and effort. Now the problem is usually the opposite: Everybody has too much data, and it’s not hard to find still more. That can lead to seemingly innocuous requests, such as “Maybe we should get more facts.” Sometimes the requests are reasonable; more often they are just a way of delaying a decision.

Alternatives. A few years ago, we asked executives in a survey whether they routinely considered alternatives when making major strategic decisions. A whopping 82 percent said no. They probably did what most companies do, which is to consider a new course of action against staying with the present one. But if you don’t get good alternatives, it’s hard to make good choices. We always suggest to clients that, when presented with a recommendation, they ask, “What alternatives did you consider and reject and why?” This simple question reinforces the need to examine more than one option and nearly always improves the quality of decision making.

Commitment. Very little is as frustrating as post-meeting conversations of this sort: “Wait—what did we just decide to do?” or perhaps, “Well, we may have decided X, but personally I’m just going to wait and see.” The opposite of this murkiness is commitment, an agreement on what the group decided and unanimous support for the decision. Decision logs—record books of every decision a group takes—can help reinforce commitment. So can explicit rules regarding decisions. Intel, for example, expects everyone to “agree and commit, or disagree and commit, but commit.”

Closure. Deciding to do something isn’t the same as doing it. If you don’t communicate the decision; establish responsibility and timelines for implementation and set up a feedback loop to monitor performance, nothing will happen. Effective closure is essential because the people trying to implement a decision can run into so many different obstacles. Companies may need to reallocate resources, adjust budgets or redefine individual responsibilities. Quick feedback is an essential part of good closure, so that executives can determine whether the decision is working out as planned.

Good processes make for better, faster decisions. And better, faster decisions produce better results.

This post was written by Michael C. Mankins, who leads Bain & Company’s Organization practice in the Americas and Jenny Davis-Peccoud, senior director of Bain’s Global Organization practice.

Decide & Deliver

Learn more about the five steps that leading organizations use to make great decisions quickly and execute them effectively.